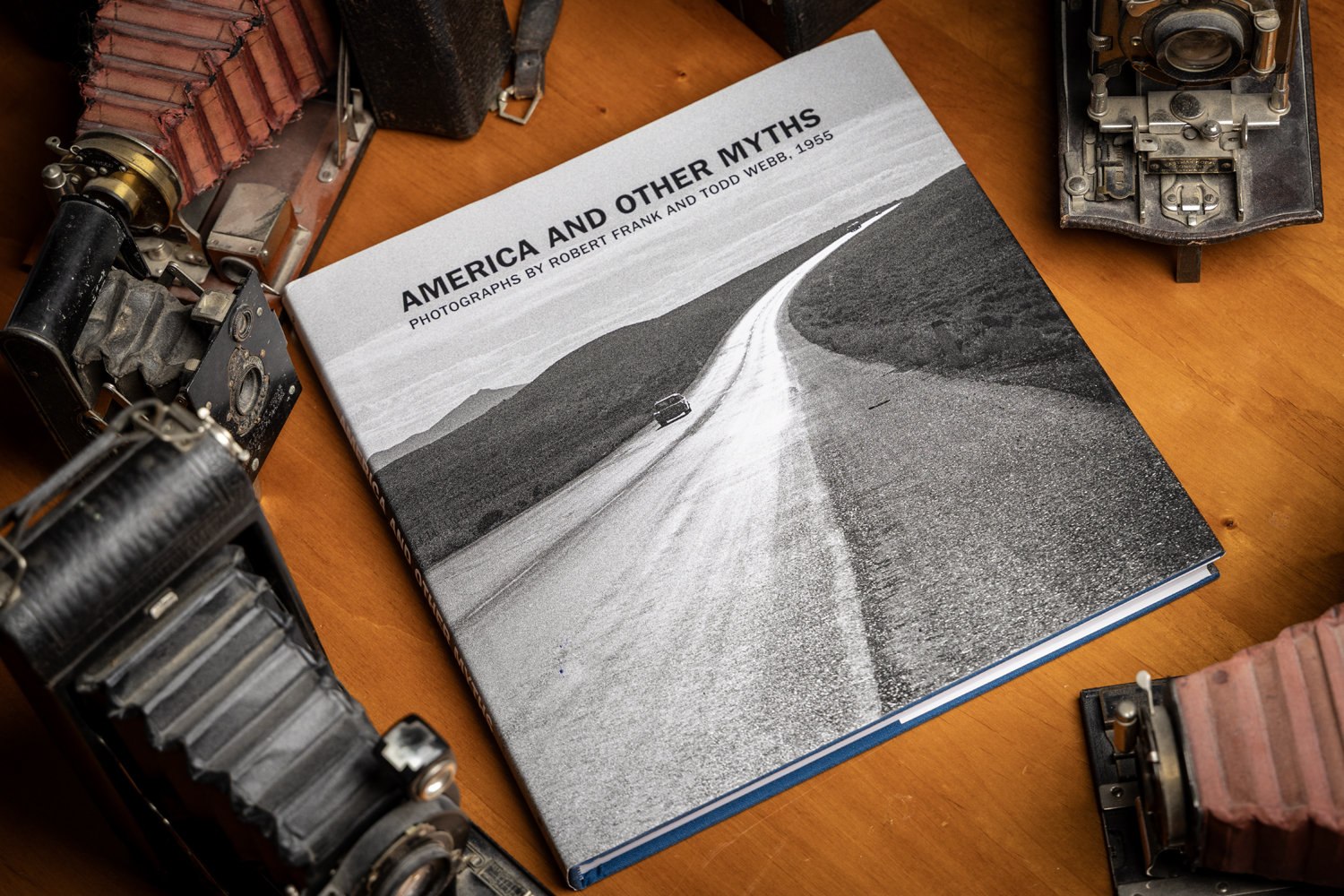

America and Other Myths: Photographs by Robert Frank and Todd Webb, 1955

Robert Frank may be the most written about and studied photographer of the second half of the 20th Century. This, despite the fact that his reputation rests on only one book – The Americans. Of course, Frank produced other work both before and after The Americans, but all of that work is known mostly in the context and shadow of his 1958 book.

The Americans is comprised of photographs Frank took while traveling the United States on a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in 1955. The book sealed Frank’s reputation as the most significant photographer of his era and continues to influence photography today. His influence was so great that it is not unrealistic to divide photography into “Before Frank” and “After Frank.” Photography After Frank, actually being the title of critic and writer Phillip Gefter’s excellent book of essays on contemporary photography.

But, another photographer, Todd Webb, also received a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in 1955 which was also to underwrite another journey across America. Today Webb is nearly as anonymous as Frank is renowned.

A new publication, America and Other Myths, Photographs by Robert Frank and Todd Webb, 1955, publishes work of both photographers from their Guggenheim trips, offering comparisons and contrasts; and showcasing the vision of each individual.

Two Photographers, Two Perspectives and Styles

As author Lisa Volpe explains, the two photographers set out with very different styles and perspectives. Frank was in search of the cultural climate of the mid-1950s, post-World War II era. He wanted to capture the way Americans were living in this new era of prosperity and innovation. He took out by car to see America, sometimes with his wife and two children in tow. Frank’s vision – a quick grab of shots, often literally shooting from the hip – matched the fast-paced and fast-changing era he was seeking to document.

Webb was largely interested in images that portrayed America’s heritage. Much as Eugene Atget had wandered the streets of Paris capturing a disappearing world, Webb wanted to depict “vanishing Americana and what is taking its place.” In his search for America, Webb planned to walk, boat and bicycle through the country, a slow pace through much of the heartland that he said would give him an opportunity to “see a slice of America, a slice right through the heart.”

Webb’s project suffered an unfortunate fate that left it virtually unknown for decades. America and Other Myths is in part an effort to correct that wrong and make amends for the fate he and his work suffered.

In 1976, just as photography as an art form was exploding across academia, museums and art galleries, Webb’s archive essentially disappeared. He had entered into an agreement with a dealer who took possession of his work, never paid him the agreed upon price and never showed his photographs. Instead, they remained locked away, unseen, until they were rediscovered in 2016.

America and Other Myths allows us to make a long overdue comparison between the two works and the photographers who created them. Despite their different approaches and styles, there are striking similarities between the photographs.

Frank Could Not Escape the Past, Webb Could Not Escape the Future

On his journey across America in search of America’s past, Webb found he could not escape the America of the future. While Frank, on a journey to document the new country that was becoming America, found he could not escape it’s past.

As Webb moved across the country, he found that his precisely laid out plan to capture classic America was frustrated by the realities of what America was experiencing in 1955.

At Cairo, Illinois, Webb began a voyage down the Mississippi River, fulfilling a childhood dream. Yet, Volpe writes, “…Webb’s reality did not fulfill this childhood fantasy or the artistic vision of his project. At locations of historical import, he found nothing but abandoned swaths of land: no people, no indication of adaptation, no lineage. People had left the past behind, both physically and in memory.”

Frank, a Jewish Immigrant from Switzerland, was fascinated by his adopted country and Americans’ love for everything new. If Webb’s project sought to preserve the past, Frank’s was bent on revealing the here and now.

But America’s past caught up with Frank and fundamentally affected his project. Venturing outside of New York and into the American South, he was confronted by the legacy of the Civil War and Jim Crow.

It was, he later said, the “first time I saw segregation” and it affected him profoundly. Some of his most memorable images were made in the South, including the iconic image of an African-American woman leaning against a wall tending to what may be the whitest baby ever photographed. His photo of a trolley in New Orleans where sets of passengers, white and Black, are separated from one another by the window frames of the trolley encapsulates America’s racial divide.

America’s prejudices turned personal for Frank at times, who found himself under suspicion and even briefly arrested by authorities because he was Jewish and spoke with an accent.

Frank’s images still resonate today in part because they reveal inescapable truths about both the racial legacy of America and about the future of the country.

Different, Yet Shared Visions

Webb’s style was much more deliberate and often formal, but some of his strongest images also resulted when his original vision came up against the realities of America.

Webb photographed a truck stop and motel at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, where a giant cowboy stands atop a sign beckoning travelers with “Where the West Begins.” Another Webb image shows the “Wharf Bar” in San Francisco, complete with oversized stylized paintings of a stemmed glass and a mug of beer on the side of the building, while a long figure stares out of the frame, arms crossed. Either could easily be slid into The Americans undetected.

Many of Webb’s images share the melancholy that are often found in Frank’s. A woman stands, back to the camera, dressed as though for a party or even a wedding, with a suitcase at her feet while in the background is a sign for the Pickwick Hotel and another for the Young Women’s Christian Association. A cowboy leans on a parking meter staring into the distance, in front of a car with a ticket on its windshield and a Safeway store in the background. In the book that photo is nicely paired with a Frank photo of a cowboy leaning against a trash basket on the street in New York.

The mythology of The Americans, is that when it arrived in the United States (It was first published in France) it was universally panned by critics. That’s not quite correct, according to Frank biographer RJ Smith. In his excellent book American Witness, he points out that Frank’s The Americans received a number of favorable reviews including from the New York Times Book Review, the New Yorker and Esquire. (As an interesting aside, in what has to be one of the most boneheaded declarations in the history of photography, Minor White, the renowned editor of Aperture and one who should have known better, declared it “A degradation of a nation!”)

In the context of the times, it’s easy to see why The Americans was not universally embraced. The Family of Man, the Museum of Modern Art’s blockbuster exhibition and ode to the universality of mankind, opened in January, 1955 and was in the midst of an eight-year world tour at the time The Americans was published. The show was the culmination of Edward Steichen’s tenure as director of MOMA’s photography department. It remains one of the most popular photography exhibits in history and the exhibition catalog in book form remains in print nearly 70 years later.

While there were certainly photographs that depicted violence and poverty, the overall tone of The Family of Man, was upbeat, playing heavily on images that lionized families, children, religion and the upward mobility that Americans were seeking and achieving.

The show suppressed the individual photographers and photographs in favor of its all-encompassing theme. The goal was to create an overall impression, not to showcase the work of the individuals.

The Anti-Family of Man

Although both Frank and Webb had photographs included in the show, neither was fond of the show.

As described by Volpe, Webb wrote in his journal, “What a blow to photography.

“The hell of it is that it is a sure fire success. And on what grounds? Being a spectacle – being overwhelming – being confusing – being trite – being publicized? Anything but being photography.”

As was typical of Frank, his assessment was more concise, but equally critical, later referring to it as “the tots and tits show.” Indeed, the show offered viewers plenty of images of adorable kids along with a fair share of mostly non-white, indigenous bare breasts.

One of Frank’s photographs included in the exhibit was a shot from outside a hamburger stand in New York, its image of six smiling, laughing young women looking out through the front window invites a contrasting comparison to the near identical composition in his photograph of the New Orleans trolley. Compositionally similar, they are worlds apart in their effect, one portraying the camaraderie of youth, while the other emphasizing the separation in American society.

It’s hardly a surprise that The Americans, with its unvarnished look at mid-century America was not greeted with great enthusiasm in a culture where the unabashed optimism of The Family of Man was viewed as the height of photographic art.

It’s hard to imagine that Webb’s photographs, although generally more upbeat and formally composed than Frank’s, would have been welcomed with much more enthusiasm had they not been lost for decades.

Both photographers went in search of America in the 1950s. And, as America and Other Myths reveals, both found a country that was more complex and challenging than either expected. Today, nearly 70 years later, the truths revealed by Frank and Webb continue to resonate and challenge.

America and Other Myths: Photographs by Robert Frank and Todd Webb, 1955 on Amazon

The Americans on Amazon

Photography After Frank on Amazon

The Family of Man on Amazon

American Witness on Amazon

Using these Amazon Links helps support this website. Thank You!