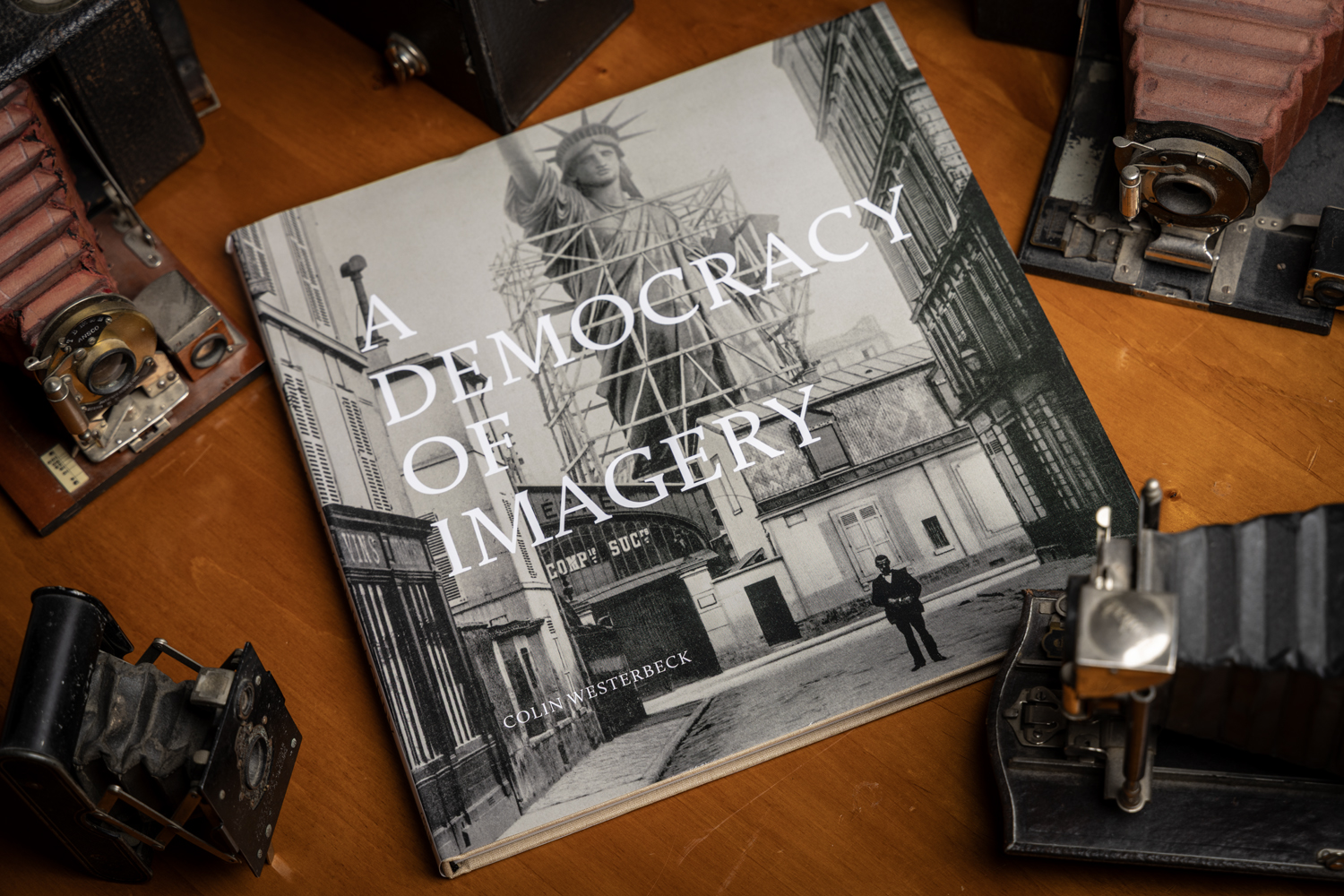

A Democracy of Imagery

In the foreword to A Democracy of Imagery, Colin Westerbeck describes the book, and exhibition that it is drawn from, as including “underappreciated photographs by famous photographers and great photographs by underappreciated photographers.”

It’s typical for photography books to showcase either the work of individual photographers or the collections of major museums, this book is the first one I own that draws from the inventory of a gallery.

Author Westerbeck worked with New York gallery owner Howard Greenberg to select a range of images from Greenberg’s inventory. There is a fair share of images from the famous, including Robert Frank, Ansel Adams, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans, Robert Mapplethorpe and Edward Steichen and many others, as well as those I was unaware of and at least one that is simply listed as anonymous.

Westerbrook, it is worth noting, is also the co-author a definitive history of street photography that is reviewed elsewhere on this site.

Rarely Seen Photos

Despite the renown of many of the photographers represented, I could find only a few images that I have seen – or at least think I’ve seen in other works.

Most of the photographs are presented with simple titles that only list the photographer, the title, the medium, the year and the dimensions.

There a handful of exceptions, where Westerbeck felt the photograph or photographer, would benefit from a brief commentary. Westerbeck’s comments are insightful and illuminating, adding important context and, in his typical writing style, the commentaries are thankfully free of academic drivel.

About 80 Photographers Represented

Just over 80 photographers are represented, most with just one image, but a handful have two, while Robert Frank and Arthur Leipzig are represented by three photographs each. Leipzig could easily fall into that category of underappreciated photographers. Born in New York in 1918, he enrolled in a class at the Photo League in 1941 hoping to pursue documentary photography. A year later he joined the staff of a liberal newspaper, PM. The newspaper closed in 1946, and Leipzig eventually moved to freelance photography where he contributed to Look, LIFE, Parade, and Fortune among others.

Frank’s three images include one from New York in 1947 that foreshadows the kind of deceptively off-balanced, casual approach that would characterize many of the compositions in The Americans. Another is a portrait of composer Edgar Varese that was apparently a commercial assignment.

The third is a 1956 photograph of his then-wife Mary Frank and their daughter Andrea. Mary is seated at a table and leans against a wall her eyes closed. She may or may not be sleeping, but her look of exhaustion is one that any parent can identify. Meanwhile Andrea stands in her crib, with a bright triangle of light illuminating one eye that stares hard into the camera. The image reveals a side of Frank’s photography that isn’t often appreciated. That he was capable of images that seared into one’s heart and encapsulated emotions that all of us have experienced.

Powerful and Compelling

There are powerful and compelling images in this book, many of which would make the purchase worthwhile.

A 1938 photograph by Margaret Bourke-White eerily presages what is about to come, with an image from a rally for Czech Nazi Leader Konrad Henlein. Henlein is not shown. Instead, she focused on the crowd of 40,000 filling the streets, standing shoulder to shoulder with their arms all raised in the Nazi salute. It is a reminder that Germany didn’t have a monopoly on fascism. It would be a disturbing image any time, but in these fraught times when democracy in America is under siege, it is particularly frightening.

A photograph from John Vachon is a departure from the better known and typical images of his fellow Farm Security Administration photographers. The upper two-thirds of the image reveals a featureless gray sky hovering over the even darker grey cliffs of the Mississippi. The foreground is a white expanse of snow with a patch in the middle, that has been cleared off to reveal the ice below and a group of five skaters silhouetted on their little skating rink.

By 1958, Berenice Abbott seemed like a photographer whose time had come and gone. Having begun as a darkroom assistant to Man Ray she had been a member of the European avant-garde of the 20s and 30s. Like many photographers and artists, she fled to the United States prior to World War II. But, Westerbeck explains that by the mid-1950s, she had not held a full-time photography job for nearly 20 years. In the late 50s she found work with MIT just as the United States was trying to catch up to Russia’s lead in the space race. IBM gave her some freelance work and the image in the book is from her project there. A wonderfully and delicately lit image, it shows a woman engrossed in a spaghetti-like tangle of wires as she works to assemble an early computer.

Bus Story by Esther Bubley

Esther Bubley, another often underappreciated photographer, is represented by a 1947 image from her series Bus Story done for the Standard Oil Company. It is a tender image of two bus patrons, a man and a woman sitting upright, but sleeping, on a waiting bench. Both have their heads down, resting on their hands in almost identical positions. This Bus Story was actually the second one done by Bubley. While working for the Office of War Information in 1943, her boss Roy Stryker had sent her by bus across the country (she did not have a car) documenting life on the road during World War II. When he moved to Standard Oil and Bubley came with him, she followed up her first story with a new one documenting the post war scene.

These images alone are well worth buying the book. But there are many more and together they form a nice addition to any photography lover’s collection.

The text is minimal, but between a brief introductory interview with Greenberg and the commentaries that accompany selected photographs, it is instructive and well-worth reading.

Buy A Democracy of Imagery on Amazon

Using these Amazon Links helps support this website. Thank You!