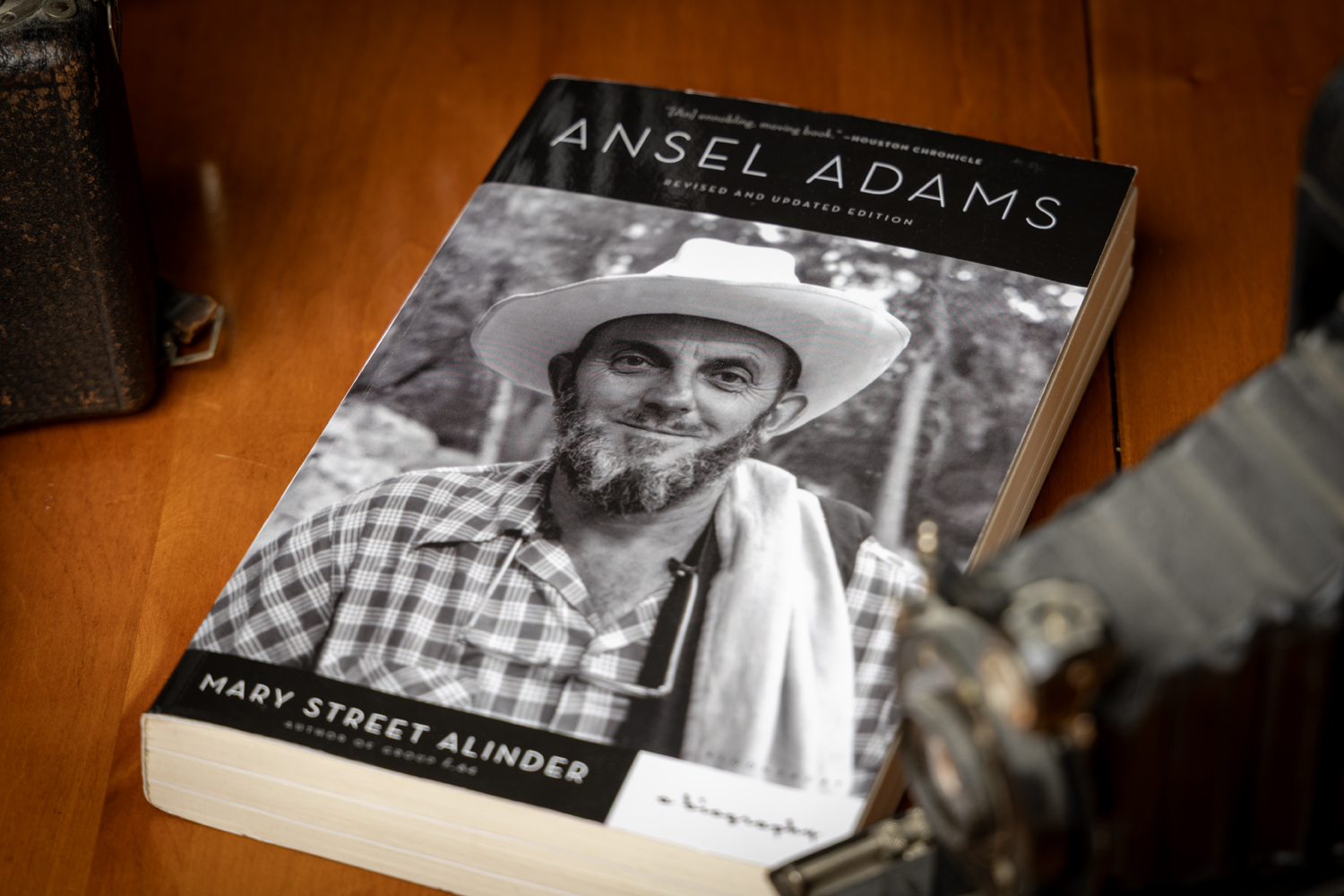

Ansel Adams, a Biography

Mary Street Alinder’s biography of Ansel Adams is loving, candid and the definitive portrait of the man who is almost certainly the most famous photographer ever.

I have always been ambivalent about Adams. In part, that reflects the influence of my college photography professor Jim Alinder. In her preface, Mary Street Alinder offers some context and insight that helps to explain that perspective, which she and Jim shared before they began their professional association with Adams.

Adams was, in the context of the late 1960s and early 1970s, seen as something of an anachronism.

“The perception of photography students was probably unanimous: rich and famous Ansel Adams was the fat cat of photography,” she writes. “In this we voted with the majority, finding that his images of a great America did not speak to us…America was napalm and Nixon, Montgomery and King…”

It wasn’t that Professor Alinder was critical of Ansel Adams’ work or discouraged his students from admiring his work. But, as a teacher he encouraged his students to develop their own vision and not attempt to mimic Adams.

‘Potboiling’

By the time I entered college in 1971, most of Adams’ greatest images were decades old and his vision could seem trapped in time. That was, in fact, an assessment that even Adams recognized, telling Stephen Shore in 1976, “I had a creative hot streak in the ‘40s and since then I’ve been potboiling.”

The 1970s and 80s were some of the most significant and creative years in photography. Universities across the United States rushed to add photography programs to their curriculum, galleries discovered the value of photographs and publishers competed to fill their catalogues with new and creative books highlighting the portfolios and projects of photographers who remain popular to this day.

An Inspiring Teacher

Jim Alinder exposed his students to the full range of photography being practiced and encouraged us to not simply repeat what had gone before, but to experiment and break new ground. Alinder himself mastered a unique and technically challenging vision utilizing the panoramic Widelux camera, but not in the traditional sense. Alinder sometimes turned the Widelux on its side to take vertical images. He also used it to take family “snapshots” and to make bemusing observations on society.

Alinder conveyed to his students an appreciation for Adams’ work, but discouraged imitation. Good advice that more photographers ought to follow. Adams’ vision was so strong and effective that almost anyone who followed was doomed to pale in comparison.

I still cringe that so many photographers, along with the photography press, seemed trapped in time, deifying one photographer and his vision, at the expense of great artists who have moved photography forward in the ensuing decades.

In recent years, I’ve gained a better appreciation for Adams’ work. It remains powerful and timeless. And, I am often guilty of trying to emulate him myself.

Renewed Appreciation

It’s not that we should dismiss Adams and his contributions. It is that we should understand that he and his vision represent a specific era in the history of photography. And, that Adams’ represents only one artistic strain that was not, even at the height of his career, the only path to follow.

Mary Street Alinder’s biography not only inspires a renewed appreciation for Adams, but also fosters a fondness and better understanding of Adams as a person and of his tremendous contributions to his two great passions, the art of photography and the environmental movement.

Insightful Backstories

For those who are familiar with Adams’ work (and who doesn’t know at least a handful of his most iconic images?) Alinder’s text offers interesting and insightful backstories to some of his greatest images. She explores the evolution that occurred during Adams’ lifetime as he printed and reprinted images, sometimes significantly modifying his approach to a particular image such as “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico.”

But this is a biography, not a treatise on film and darkroom printing, and its value lies in illuminating the man. Adams’ images too easily overshadow Adams the person. What emergences from Alinder’s book is a portrait that is more complex and challenging than the standard mythology that has been popularized over the years.

In peeling away the layers, Alinder gives us a portrait of an imperfect but ultimately lovable human being.

Mary Alinder’s role in Adams’ world does not fit into a simple category. Jim Alinder was recruited by Adams to serve as the executive director of Carmel’s The Friends of Photography, which Adams had founded to promote the art of photography and the work of photographers who often struggled to receive recognition.

In Mary Alinder, Adams found a person who could meet his multiple needs.

As she writes in the preface, “Ansel hired me for a number of reasons, the first being that we got along so well. Second, I was knowledgeable about photography, both its aesthetics and history, and possessed the finely honed organizational skills of a working mother. Third, he was curious about all things medical; during my year at the hospital (Alinder holds a nursing degree), it was not unusual for him to stop by my area for a chat. In me, he now had a personal nurse. Fourth, my avocation is serious cooking, and Ansel’s was eating. Finally, and most important, Ansel had not yet written one word of his autobiography, although his 1978 deadline had come and gone. With my background as an editor and writer, I was to ‘make Ansel write his autobiography.’ And I did.”

Co-Authored Adam’s Autobiography

In fact, Alinder’s contribution to Adams’ autobiography was so significant that it earned her credit as co-author.

Adams’ images, like all great photographs, don’t need detailed explanations that might only serve to distract from the images.

But, Adams’ himself benefits from Alinder’s dive into his life story. What emerges is a man who was deeply committed to the art of photography and securing its place firmly among the arts. While Alfred Stieglitz is often credited with defining photography as art, the center of Stieglitz’s world was always Stieglitz.

Adams could be rigid and opinionated in what styles of photography he considered art, but he was generous in promoting the medium and his fellow artists, without demanding the limelight. With the confidence that only someone who has a firm grasp on their own artistic vision has, Adams was a tireless advocate for photography. Together with his friend Beaumont Newhall it could be credibly argued that they literally pushed and pulled major museums and galleries into accepting photography as a medium equal to that of painting, sculpture and other traditional arts.

An Environmental Warrior

Similarly, Adams contributed enormous portions of his life to protecting the environment. If he did not create the environmental movement, he certainly could lay claim to bringing it into the mainstream of America’s social and political life. His generosity with his own images played no small part in making the Sierra Club financially viable and is an obvious visual reminder of his commitment. But less well know is just how much time and effort he spent behind the scenes working to protect America’s natural areas.

Mary Street Alinder’s biography gives us the definitive portrait of the man who continues to influence photography today. And, while that influence leads to far too many overwrought, melodramatic imitations by would-be artists, we should remember that the failures of those imitations should not be held against the originals. Instead, what the biography shows us is that photography and the environmental movement would not be what they are today if it were not for the Adams’ lifelong, unrelenting work.

Buy Ansel Adams, a Biography on Amazon.

Also recommended: Ansel Adams, 400 Photographs and Ansel Adams in Color

Using these Amazon Links when buying books helps support this website. Thank You!