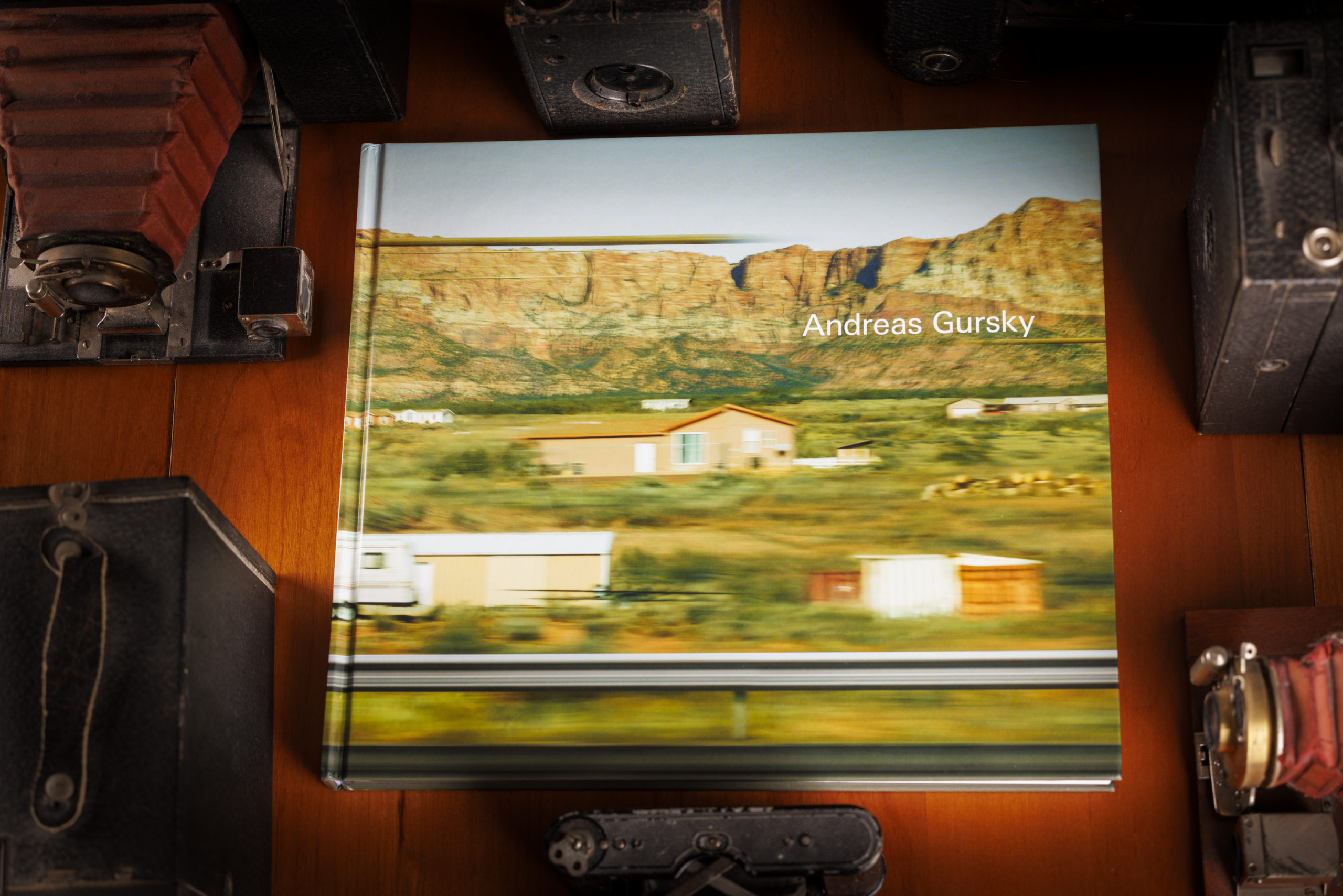

Andreas Gursky

One of the most significant changes in photography over the past forty years has been the creation of photographs specifically for display on the walls of museums.

For most of the history of photography, the primary medium for the public to view photographs has been the book or magazine. Photographs taken with the intent to be published, but found their way onto the walls of galleries and museums, repurposed for exhibitions.

Great photographers of the 20th century, who were rightly considered artists, are mostly known for images that were intended for and first appeared in print – often in the picture magazines like Life, Stern, Paris Match and Stern. This was true of Henri Cartier-Bresson, W. Eugene Smith, Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White and Robert Capa, to name just a few examples.

Other works were first created for commercial assignments or sponsored by foundations or government agencies. The Sierra Club was a patron of Ansel Adams. Their support helping to make it possible for him to earn a living. The most famous sponsored projects were the depression-era government agencies – the Farm Security Administration and its successor the Office of War Information.

Robert Frank, the most influential photographer of the second half of the 20th Century, is known primarily because of his book, The Americans. As publishing costs dropped, in the 70s and 80s the photographic book rose in importance as a way for photographers to showcase their work, especially for documentary photographers.

Of course, there have always been exceptions. Edward Weston’s photographs were created with the intent to be displayed in galleries and sold to collectors. Weston resisted having his work printed because he did not feel that most printing processes of the time could do justice to his images. But, the photography collections of most major museums would be considerably less rich without images that were taken primarily for publication.

Andreas Gursky’s work, like that of many other contemporary photographers, has always been destined for the wall. Gursky’s images are massive. Rivaling, and in some cases exceeding, the size of a typical painting. Rhine II, among his most famous images, is nearly 12 feet long by six feet tall.

Andreas Gursky, published in 2018, offers an extensive selection of his photographs from the 1980s through the 2010s. It includes an introduction and overview titled “Andreas Gursky: Four Decades” written by Ralph Rugoff, the director of the Hayward Gallery, which is the publisher of the book.

It also includes a commentary, “The ‘Authentic Image of the Rhine’: A Photographic Icon my Andreas Gursky” written by Gerald Schroeder, as well as “The Order of Things” by Brian Sholis and a short piece by Katharina Fritsch titled “Andreas.”

While the commentary is thoughtful, I was reminded that the act of explaining often undermines the experience. Detailed scholarly examinations are almost mandatory for any portfolio of a photographer’s work. Unfortunately, artists, artworks and viewers do not always benefit from these texts.

“You want me to say it worse?” was the response Robert Frost once gave to a person who asked him what one of his poems meant.

As I read the texts in Andreas Gursky, I couldn’t shake the feeling that while they contain interesting insights, they also border on explaining Gursky’s images worse.

Admittedly, that’s a little unfair to the commentary in Andreas Gursky. The essays contain interesting facts and important context. But it would be a mistake for the reader to get too caught up in the text and neglect the images, which offer powerful visual experiences with or without explanation.

The most rewarding section is a transcript of a conversation between Gursky and fellow photographer Jeff Wall. Rather than attempt to overintellectualize his work, Gursky and Wall simply talk about the photographs, his evolution and his influences.

The conversation ends with the best statement in the book, “I want to conclude by saying that seeing and the imperative to find images leads me to my subjects, and not the other way round.”

Naturally, when the dimensions of a photographer’s work are measured in feet rather than inches, it is difficult to produce a book that can do them justice. One of Gursky’s strengths, however, is that many of his images remain powerful when reduced to a fraction of the size of the originals, even if the reader cannot quite sense the scale and depth of detail that the originals contain.

For those unfamiliar with Gursky, it is important to understand that many of his images are painstakingly retouched and, while they appear as pristine representations of their subjects, those subjects have often been significantly altered.

His iconic Rhine II is a particularly notable example, having been edited to remove almost all traces of manmade structures, including a massive power plant that actually sits across the riverbank from the photo’s vantage point. Gursky has edited the scene to leave only three narrow bands of grass. The two in the foreground are broken up by a pathway that bisects the lower third of the image. The opposite side of the river is defined by the third band of green. The image itself is split in two with a gray, almost detail-less sky covering the top half of the image.

The result, though, is an image that appears perfectly natural and quite beautiful in its simplicity.

Gursky is a masterful observer of the modern world. His “99 Cent,” shows the interior of one of the ubiquitous dollar stores that now represent the most common store in America’s small towns. It is an era-capturing commentary on modern consumer culture in the late 20th and early 21st century.

With its seemingly endless aisles of candy bars, snacks, juice, condiments, and other foodstuffs receding into near infinity, it is as emblematic of today as the photographs of the Farm Security Administration were of the 1930s, or as Robert Frank’s images were of America in the 1950s.

“99 Cent” is just one example of how Gursky has captured the way we live today. His “Illinois, Stateville 2002,” “Greeley 2002,” “Amazon 2016,” and “Frankfort 2007” all serve as near-perfect summations of mass incarceration, industrialized food production, consumer consumption, and modern airline travel, respectively, in today’s world.

For decades photographers like Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Joel Meyerowitz, Vivian Maier and Elliott Erwitt turned to the street to document and critique society. But today we live in a world that has become increasingly homogenized. Social interactions have turned inward and the vibrant street life portrayed in the past is no longer emblematic of the way people live today. Americans and much of the rest of world increasingly live out their lives online, secluded within their homes. Gursky’s images, which are often either devoid of human subjects, or reduce the subjects to near objects, fit this isolated, insular era perfectly.

When living in the present, it is difficult to predict what art will stand the test of time. Much of post-modern and post-post-modern photography may well fade into well-deserved obscurity. But it is likely that Gursky’s work will remain as revealing and iconic commentaries of how life is lived today and what that holds for the future.

A note on availability.

Unfortunately, Andreas Gursky, is only available in limited editions and the cost has skyrocketed from the time when I first purchased the book. (Currently selling for $350 on Amazon.) The Amazon listing also, unfortunately, appears to incorrectly list a paperback version for $28.95, but the link actually goes to an unrelated 1922 novel.

There is a new (2023) book listed that sells for a slightly more reasonable $75 – Visual Spaces of Today, Andreas Gursky. However, the Amazon description is not in English and since I don’t own the book, I cannot vouch for it.