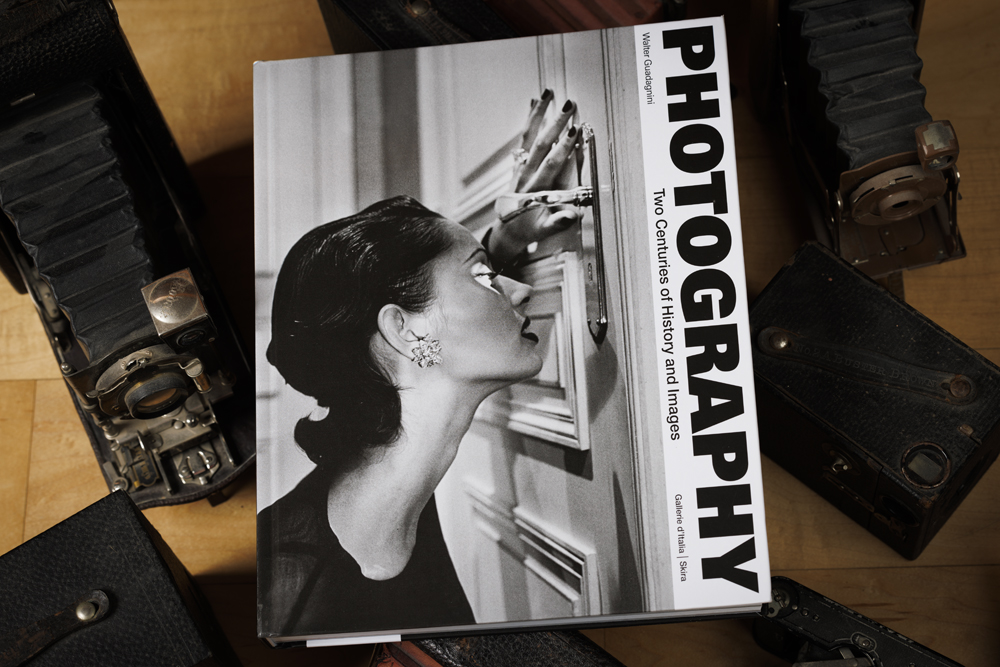

Photography: Two Centuries of History and Images

In an era when more than 1,000 images are uploaded to Instagram every second (a statistic that is no doubt obsolete by the time you read this) it is hard to grasp that less than 200 years ago not a single photograph existed in the world.

In Photography: Two Centuries of History and Images Walter Guadagnini has undertaken the task of not only documenting the history of photography over those 200 years, but also of placing photography into the social context across those two centuries.

Guadagnini delivers a very readable tour of photography in context. Although he discusses the contributions of individual photographers, his history is much more than a “great person” recounting of one artist after another. Instead, he concentrates on trends in photography and in society, offering illuminating and understandable explanations of how photography influenced the world and how the world has influenced photography.

Photography Created Celebrity

For example, Guadagnini details how photography created celebrity. With the invention of photography, for the first time in history people could actually see what world leaders, performers and others looked like. In turn, that quickly created expectations that everyone should be able to see the people that were shaping the world.

From 1860 to 1862 between two and three million portraits of Queen Victoria were produced. A number that becomes even more staggering when placed in the context that barely 20 years earlier, not one photograph of Victoria or any other king or queen existed.

Each of the 16 chapters in the book focuses on significant trends, times and photographers that helped define photography. Within each, is a section that usually highlights a significant technological development or a major change in how photography has been perceived. Unlike some surveys or histories of photography, both Guadagnini and his collaborator, Monica Poggi, avoid academic jargon to produce text that moves quickly and clearly.

Excellent Albums of Photographs

Possibly the most rewarding aspect of the book is a series of three “albums” that reproduce significant examples of key photographs from each era. The 9½ by 12-inch format of the book allows for large reproductions which, in keeping with most books from the publishing house Skira, are beautifully reproduced.

In an unusual and, frankly baffling decision, the albums are printed in reverse chronological order, with the most recent photographs in the first album and working back to the earliest known photograph at the end. Still, this does nothing to subtract from the volume, although I’m not sure it contributes anything either.

One quibble is that in the final chapters, Guadagnini often resorts to long lists of significant photographers in his discussion of more recent trends. It has the effect of turning much of the text into little more than shout outs to contemporary photographers. I understand the desire to recognize as many photographers as possible and, of course, one of the risks of any writing about contemporary art is that it is difficult to predict which artists will stand the test of time.

But the lists contribute little to the overall high quality of the text. At best, they provide a launching point for interested readers to discover photographers they may not be aware of.

Worth Considering: A Four Volume History

Although this history is a stand-alone volume, I would note that Guadagnini served as the editor for Skira’s massive four volume 2015 survey of photography that is still well worth the considerable investment if you can find them.

In some ways, this is something of a condensed version and postscript to that work, although it stands alone and does not require reading the other work to enjoy this one.

Daguerre and the Birth of Photography

Photography: Two Centuries of History and Images begins in 1839 with the public announcement in France of Louis Daguerre’s Daguerreotype. Photography was nearly simultaneously invented by about two-dozen individuals. But, history and tradition awarded first place in the race to Daguerre, largely because the French government had the wisdom to compensate him in exchange for making the invention available to the public, thus enabling it to be almost instantly popularized.

Daguerreotypes were one-offs. The images were fixed to a single opaque but highly polished surface that appeared either as a positive or a negative depending on the angle that the image was held. Because there was no “negative” involved, individual images could not be reproduced except by rephotographing them. Since the surfaces were not very light-sensitive, photographs of people were difficult to make, as the subjects had to hold still (or be held still by various devices). But the technical challenges fell by the wayside over the next several decades as improvement after improvement make the process easier and ever more popular.

George Eastman’s Invention

In 1888, when George Eastman patented and released his first Kodak camera, the technology of a rolled, flexible negative film that could be used to make virtually unlimited positive prints became the technology that would dominate photography until the birth of the digital age.

Guadagnini makes clear that it is no exaggeration to say that photography changed the world and that those changes continue today. The Daguerreotypes created an insatiable demand that continues to this day, with each technological change making it easier and cheaper to disseminate images.

It is no exaggeration to say that the social media revolution of the 21st century has been driven by photography. It is the sharing of photographs that dominates virtually every social media platform today.

The idea that photography exactly reproduced nature gave birth to the stereotype that the camera could not lie. A concept that continues into the 21st century, even though it was never quite true. Today this convention is being upended by the Artificial Intelligence revolution that may finally put to rest a myth that we have all lived with for nearly two centuries.

The Art World Upended

Photography upended the art world. This interloper was seen as a threat by 19th century painters, who quickly saw that their world would never be the same. As photography reached to become an equal in the art world, it changed the aesthetics of painting and sparked a creative 20th century re-invention and cross pollination that gave us modern and postmodern art.

Guadagnini, beginning with his chapter, “I want to be a machine,” shows how pop art merged art and photography. Photography – rejected by the art world in the 19th century – has become the center of much of modern art.

Birth of Straight Photography

Leading photographers of the late 19th and early 20th century were caught in a trap of trying to emulate painting. In the United States that ended with one of the most significant and revolutionary changes in the aesthetics of photography – the work of Paul Strand, which gave rise to the aesthetic known as “straight photography.”

Guadagnini writes of Strand, “…he was unfailingly guided by the same principles of absolute fidelity to the essence of photography language and its potential utopian purity.”

Strand, with a significant assist from Alfred Stieglitz and later reinforced by the f64 group of photographers, set in motion the acceptance of photography as a unique art form, that did not rely on painting but rather stood on its own. He didn’t merely accept the mechanical and chemical nature of photography, but saw that mechanical and chemical nature as integral and essential elements that make photography a separate and distinct was of seeing.

Photography was Born Whole

This recognition of Photography as its own medium allowed it to flourish over the past 100 years, set free to establish itself on its own terms.

The most eloquent summation of photography as a unique medium may have been written nearly 60 years ago by John Szarkowski in The Photographer’s Eye, “The history of photography has been less a journey than a growth. Its movement has not been linear and consecutive, but centrifugal. Photography, and our understanding of it, has spread from a center; it has, by infusion, penetrated our consciousness. Like an organism, photography was born whole. It is in our progressive discovery of it that its history lies.”

Photography: Two Centuries of History and Images, takes us on the fascinating and illuminating journey through that history, its aesthetics and its impact.

Photography: Two Centuries of History and Images on Amazon

John Szarkowski: The Photographer’s Eye on Amazon

Skira History of Photography Four Volume Set on Amazon

Individual Volumes

The Origins 1839-1890 (Not currently Available New)

A New Vision of the World 1891-1940

Using these Amazon Links when buying books helps support this website. Thank You!