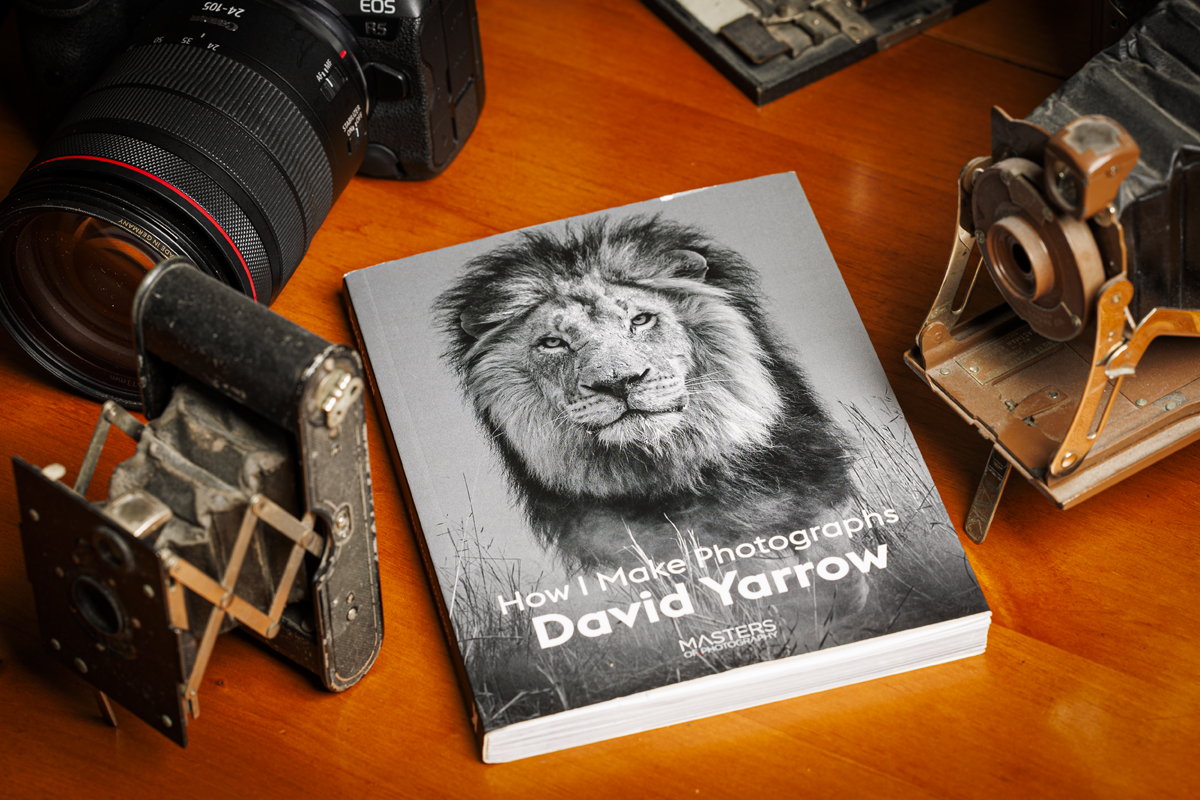

David Yarrow: How I Make Photographs (Masters of Photography Series)

The photography workshop has long been a way for photographers to monetize their work, particularly as magazine and book markets shrink under pressure from electronic publishing and social media.

But the workshop circuit is grueling and time consuming. Even great photographers are not pop stars capable of filling stadiums with fans shelling out hundreds to hear them talk. In addition, not everyone can travel to an in-person workshop or afford the steep cost of many workshops.

In 2014, Aperture Foundation started publishing the Photography Workshop Series, which attempts to create an experience similar to an in-person workshop through books featuring the work and commentary of well-respected photographers.

In 2019, publisher Laurence King joined the market with their series grouped under the title of “Masters of Photography,” with the first volume featuring Joel Meyerowitz. This was followed by a second book focused on Albert Watson.

Most recently, the third in the series featuring wildlife photographer David Yarrow has been published. King has been fairly slow in rolling out the books and it seems that their main focus is on a much more costly companion series of video courses. But, I’m a book person, so I’m choosing to highlight the book series and hope they will step up the pace of publication.

If you are interested in the videos, they can be found at www.mastersof.photography. The current video series includes courses from Meyerowitz, Watson and Yarrow, as well as Paul Nicklen, Nick Danziger and Steve McCurry. I expect we will see companion books from Nicklen, Danziger and McCurry eventually.

David Yarrow began his photography career as a sports photographer, first covering soccer for a local magazine in Scotland. He managed to parlay that into accreditation from the Scottish Football Association to attend the FIFA World Cup in Mexico in 1986. As he discusses in the book, Yarrow reached a crossroads in his career and set photography aside in the late 1980s to work in the financial industry. The financial crash of the 2000s forced him to reassess what he really wanted to do with his life. He chose to return to photography, pursuing a career that would concentrate on wildlife and the natural world.

As someone who packed away his cameras in his twenties in order to take jobs that would offer enough pay to raise a family, I can respect and admire Yarrow for his choices both to give up and then to return to photography.

Yarrow works primarily in black and white. His images of wildlife are graphic and often deceptively simple compositions. The eyes in a Yarrow photograph stare with an intensity that reminds you that eyes are not only windows to the soul of humans but of animals as well. The connection these eyes make remind us what a privilege it is to share this earth with these marvelous creatures. Yet, at the same time, there is no mistaking that the gaze of a Yarrow wolf, ape, lion, bison or bear is a reminder that the flip of a claw, the tear of a fang or the stomp of a foot can separate soul from body.

Even when he shoots in color, Yarrow’s images are sparse – cranes whose white bodies fade into snow, with only the black of a neck, tail and legs and a flash of their red crowns to define them. A polar bear lumbers across the landscape, which is so overcast that the background of sky and mountain are almost monotone. A tiger, half submerged, floats in a sea of black.

Yarrow’s success has placed him in demand for commercial photography and the book includes a number of images that he has composed using human models and trained animals. They are intriguing and impressive, but these images, which are essentially productions worthy of a Hollywood movie set, don’t have much relevancy to the average reader. Put model Josie Canseco and a trained wolf in a convertible in Monument Valley and you better come back with a great picture.

It’s much the same opinion I have when I look at an Annie Leibovitz production. I respect the amount of planning and work that goes into these productions, but they don’t have much relevance to my photography.

As far as the book goes, and I’ve written about this before with the Aperture workshop series, the real value of these volumes is not so much the words of the photographers, but in the opportunity to obtain a low-cost portfolio of a great photographer’s images.

Certainly the texts are valuable and can add context, but candidly they begin to sound a whole lot alike. There are the requisite stories of challenges overcome, the practical advice that often boils down to keeping the images simple and pared down and paying attention to the background, the self-evident observations that it is cold shooting penguins in Antarctica and lots of exhortations to follow your own vision.

Robert Adams (whom I believe may be, hands down, the best writer on photography ever) wrote in his book, Why People Photograph: “Years ago when I began to enjoy photographs I was struck by the fact that I did not have to read photographers’ statements in order to love the pictures. Sometimes remarks about the profession by people like Stieglitz and Weston were inspiring, but almost nothing they said about specific pictures enriched my experience of those pictures…

Adams then references this: “…as Robert Frost told a person who asked him what one of his poems meant, ‘You want me to say it worse?’”

For the most part, these photo workshop series, as well as individual books where photographers attempt to explain their work and how they got a particular shot, may tell interesting anecdotes and provide some insight into the photographers thought process, but like in-person workshops, the main value is usually in providing inspiration to reenergize our own work.

I believe this to be particularly true in the case of photographers who work in nature, sports, documentary or any genre where we are dependent on the subject to make the photograph (which frankly covers almost all photography that I am interested in).

A personal confession here: I am a picture “taker” not a picture “maker.” I greatly admire photographers like Jerry Uelsmann, who carefully constructed his photographs from his mind’s eye. I’ve even tried to emulate him and others, but my attempts always ended up looking contrived and silly.

I am more of the Garry Winogrand “I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed,” mindset.

I feel that often photographers, when asked to discuss their work, are compelled to emphasize their creative control of the situation at the time the photograph is taken. A lot of great photographs are the result of chance and luck. Having the skill, vision and experience to recognize and capitalize on these lucky encounters is often what makes a photograph great, but that cannot be taught in a workshop or workshop-style book or video. And, frankly, reading about the circumstances under which a unique photograph was taken is unlikely to be of much practical use to the reader.

It’s not that reading these books is a waste of time. There is always a decent share of sound advice. In some cases it is informative to learn what was involved in capturing a certain picture, especially one that seems particularly unusual or complicated.

In the best books, the texts enlighten us to what the photographer hoped to convey and how he or she went about doing that.

But my advice is to buy these books for the pictures first and if you benefit from the text, consider that a bonus. It is Yarrow’s photographs that make this book worth buying.

David Yarrow: How I Make Photographs on Amazon

Albert Watson: Creating Photographs (Masters of Photography) on Amazon

Joel Meyerowitz: How I Make Photographs (Masters of Photography) on Amazon

Aperture Photography Workshop Series on Amazon

Why People Photograph by Robert Adams on Amazon

Using these Amazon Links when buying books helps support this website. Thank You!