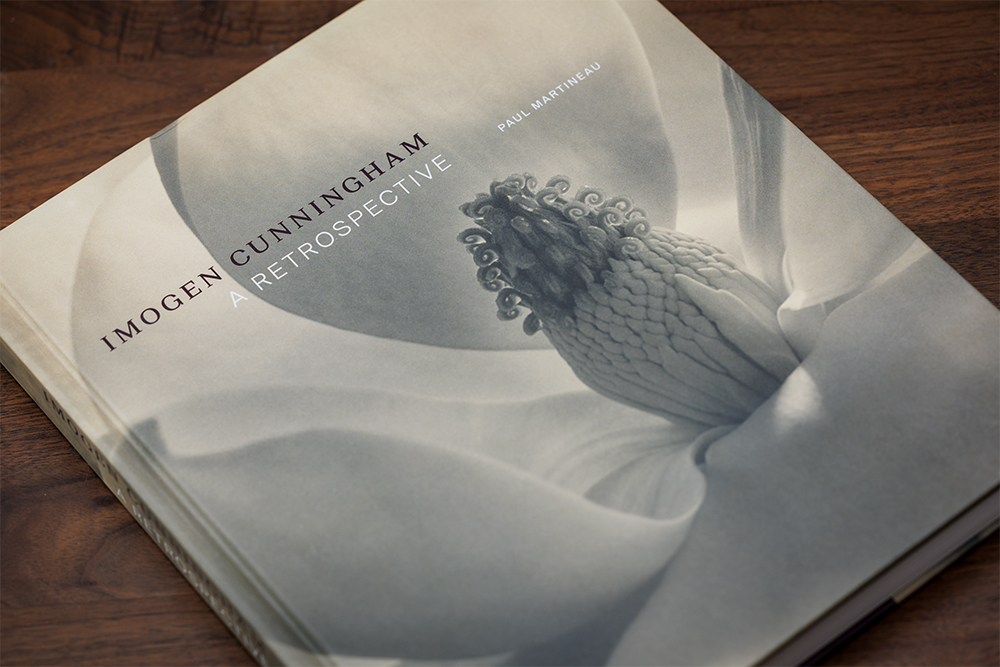

Imogen Cunningham: A Retrospective

Imogen Cunningham was one of the most creative, versatile, influential and possibly underappreciated and underrated photographers of the 20th Century.

Born in 1883, her career extended from the era of Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand, through Edward Weston and Ansel Adams and into the 1970s, yet it was only late in life that she began to receive the recognition that her male contemporaries and colleagues had been afforded decades earlier.

A beautiful book published in 2020, Imogen Cunningham: A Retrospective, printed in conjunction with a Getty Museum exhibition of her work offers a well-printed, if overdue, selection of her life’s work, along with thoughtful commentary that gives insight and helps encapsulate a career that encompassed the era of Pictorialism, spanned the life of Group f64 (of which she was an original member) and continued until she was in her 90s.

Most artists careers seem to follow a bell-shaped curve – after an early period of experimentation and learning, they exhibit a burst of creativity that establishes their careers and position in the art world. Although many remain active for decades, it is often their early work that they are remembered for. Later work can seem repetitious, as though they are simply treading water, or worse yet – embarrassingly desperate attempts to remain relevant.

It’s as if one can play the same hits over and over again, as Ansel Adams admitted that he did. Some become a caricature of their former selves, constantly and desperately seeking to recapture the attention and relevancy they once had.

A few choose to simply exit the stage, having had their say. That is something I’ve admired about Grace Slick and Robert Frank. Slick left the world of rock and roll, saying rock was for the young. Frank, having said what he wanted to say in The Americans, moved on.

But, every once and a while the world gives us artists who never stop exploring and creating, but resist the temptation to repeat themselves. That is one reason why I admire Van Morrison, a middling rocker who is likely to be remembered as one of the great composers of the modern era.

Cunningham, over her 93 years, seemed to approach photography with the same enthusiasm and sense of experimentation that originally attracted her to the craft.

When she was 75 she divided her career into three periods, beginning with her early Pictorialism days, concentrating on soft-focus painterly portraits and landscapes that sought to convey a mood and, as was popular at the time, often evoking mythology and romantic poetry.

In the early 1920s she embraced the straight photography ushered in by Paul Strand and ultimately defined by her and her colleagues in Group f64. She, along with Edward Weston and Ansel Adams formed the founding trinity of the group.

Taking their name from the smallest standard f-stop of cameras at the time, these photographers embraced photography as a unique medium, distinct in its own right and entitled to judgment not by the standards of other arts, but by its own standards.

John Szarkowski, the influential curator wrote in his book, The Photographer’s Eye, encapsulated the guiding principle of straight photography, writing “Like an organism, photography was born whole. It is in our progressive discovery of it that its history lies.”

Szarkowski’s point being that photography was never a weak cousin of drawing or painting, but always an art in itself that has its own intrinsic characteristics.

Paul Strand, Group f.64 and others dominated photography for much of the 20th Century and their influence remains strong today.

Cunningham’s later period seems a natural outgrowth of her earlier work. She often returned to portraiture, which had sustained her at the beginning of her career. But her portraits merged her early sensibilities with her technical mastery of light and straight photography. While never abandoning the aesthetics of straight photography, she was unafraid to experiment. Throughout her career there are examples of multiple exposures made by superimposing one image over another. In her later years, she continued to play with the technique.

Playfulness can be an apt description for Cunningham’s approach to photography. Not as one who is unserious, but as one who is unafraid to challenge conventions and willing to accept happy accidents that lead to great images.

Throughout her career she was willing to violate the rules and experiment with her techniques and with her composition and posing. Some of her most interesting photos reflect a spontaneity that was often lacking in other Group f64 images.

There are quotes from her fellow Group f.64 members, criticizing her craftsmanship. The comments have an air of male superiority, but if Cunningham’s prints did not display the care of an Edward Weston or an Ansel Adams, it is unlikely due to any inferior mastery of technique. After Cunningham decided to take up photography, and on the advice of the head of the chemistry department at the University of Washington, she majored in chemistry and studied physics. A curriculum that gave her a solid foundation in the technical aspects of film, printing, lenses and light.

One suspects that if the quality of her prints did not match those of Weston or Adams, it probably wasn’t because she couldn’t, but more likely because she was more interested in her subjects than her prints.

In her final years, Cunningham was still taking on new projects. The most notable was After Ninety, a series of portraits of persons aged 90 or over, that was published posthumously in 1977, shortly after her death.

Those final years also afforded her some of the recognition that she deserved, but which had escaped her during much of her lifetime. Living in San Francisco at the height of the Peace and Love era, Cunningham became something of grandmother deity to many young photographers.

Cunningham even appeared on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson not long before her death.

In her history, Group f.64, author Mary Alinder summed up Cunningham in this way, “Always relevant and real, Imogen found new fans in each crop of young photographers who gathered around her to listen and learn…her door was always open. During the 1960s, Imogen opposed the Vietnam War, dressed in perfectly ironed “granny dresses” … and was chauffeured by young friends in a very PC Volkswagen Van.

“The women of Group f.64, but most unfairly Imogen, have been assigned a lesser place in history because they were not writers, as were Ansel (Adams), Edward (Weston), and for a time Willard (Van Dyke). The voices of those men still speak clearly from the pages of books and magazines…It is far easier to understand these men’s contributions to photography; none were shy of telling us. Imogen Cunningham instead relied on her photographs, which are infinitely more challenging to read.”

Thankfully, with the publication of Imogen Cunningham: A Retrospective, photographers have an opportunity to read and appreciate her work.

Imogen Cunningham: A Retrospective on Amazon

The Photographer’s Eye on Amazon

Group f.64 on Amazon

Using these Amazon Links when buying books helps support this website. Thank You!