Carrie Mae Weems

Carrie Mae Weems may be the most interesting photographer practicing today. Not the most interesting Black Photographer nor the most interesting Woman Photographer, but simply the most interesting photographer.

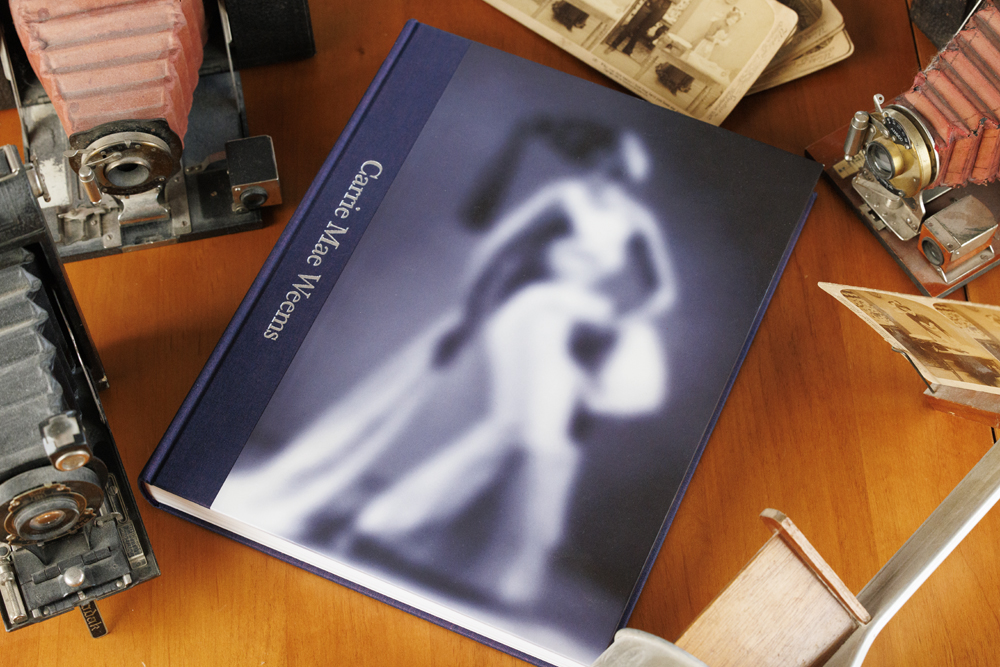

Looking at the beautiful catalogue (Carrie Mae Weems: A Great Turn in the Possible) created for the European exhibition of Weems’ work, sponsored by Fundación MAPFRE, I had a similar reaction to the first time I saw Robert Frank’s The Americans, back in the 1970s. Not because of the style of the work, which is radically different from Frank’s, but because of the significance and clarity of vision.

Of course, comparing anyone to Robert Frank risks accusations of hyperbole. After all, Frank is acknowledged as perhaps the most significant and influential photographer of the second half of the 20th century. Frank’s work changed the way we all look at photographs and photography has not been the same since.

But looking through the book and soaking in Weems’ images I did have much the same feeling that I had when I discovered Frank. That is, that I was looking at the work of a unique artist. Like Frank, Weems has something to convey and she does it with eloquence and power.

While Frank made his statement in a single ground-breaking volume, Weems is a prolific artist whose work spans decades. Weems has a lot to say and she continues to say it. It seems as though each new project peels away another layer, as she gradually and methodically works toward revealing the core that is the center of America’s complex relationships with race and gender.

In devoting much of her art to championing the humanity and dignity of society’s victims, one can’t shake the feeling that Weems herself has been a victim of the same biases that her art illuminates. Looking through my own collection of photography histories and anthologies, I find she is too often ignored or relegated to a generic list of contemporary photographers.

For those who are unaware of Weems’ work, she is a multi-media artist. That is, her projects are not limited to still photographs, but often include film, the written word, constructed rooms, wall hangings and even porcelain. But the core is the image.

Weems was born in 1953 in Portland, Oregon. She received her Bachelors of Fine Arts in 1981 from the California Institute of the Arts and her MFA from the University of California, San Diego.

It is understandably hard to convey her three-dimensional and video pieces in the confines of a book, but the exhibition catalogue does an outstanding job. Having never had the opportunity to view one of Weems’ installations in person, I felt that the book still captured the essence of her work, even if the experience cannot possibly be as rich as being fully immersed in her art.

The book, and I presume the exhibition, is a bit of a “greatest hits” selection of some of Weems’ best known and most powerful work.

In her “Kitchen Table Series,” Weems plays the central character, an anonymous and universal African-American woman who moves through a domestic drama familiar not just to Black women but to women of all races and nationalities.

In her “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried” series she repurposed ethnographic “scientific” images, images of slaves and former slaves, and other stereotyped imagery, overlaying them with text that critiques and informs the images. The words serving as commentary and counterpoint to the perceptions of Africans and African-Americans that have been perpetuated in white culture.

Weems’ images in “Constructing History,” take the form of tableaus that seem to recreate behind-the-scenes film sets that are not quite literal recreations of significant events of the 1960s.

For example, one image – The First Major Blow – portrays a white couple seated in the back seat of a convertible. The woman appears to be waving to an admiring crowd, while the man looks over and smiles. They are the Kennedys and yet not the Kennedys.

“The Assassination of Medgar, Malcom and Martin,” shows a man prone on a slab, two other men stand on either side, looking down at him with a mixture of concern and distress, while a woman in a headscarf stands behind him, cradling his head like a Madonna in a modern-day Pieta. Barely within the frame is a movie dolly that surrounds the tableau, as though filming the scene.

The scenes are sufficiently recognizable to spark mental images and memories of the actual events, yet sufficiently different to drive home a message of universality – a reminder that the actual historical events carried meanings that transcend a single point in time and continue to influence us today.

In “The Hampton Project” Weems used the photographs of Francis Benjamin Johnston from the Hampton Institute as a foundation to form a critique of efforts to “help” mostly African-American and Native American youth be absorbed into the dominant white culture. Johnston was a feminist and non-conformist who took up photography at the end of the 19th Century.

At the time, Johnston’s work was meant to showcase a school that, with good intentions, sought to “lift up” their students. But those efforts, popular at the end of the 19th and continuing for much of the 20th century, not only in the United States, but in other countries like Australia and Canada, were tainted by stereotyping and the assumption of the superiority of white culture and the inferiority of minority culture and abilities.

In her recent “Painting the Town” project Weems became fascinated with the boarded up and painted-over cityscapes that emerged in the aftermath of the George Floyd murder and protests. Her images are reminiscent of abstract paintings and the photographs of Aaron Siskind, but with a decidedly Weems’ take.

She was interested, she explains, in the way cities impacted by Floyd’s murder and resultant demonstrations were beginning to paint over the scars, “as a way of sort of dealing with the demonstrations and burnout that was happening almost every day…Just slapping this paint on becomes this thing. So, I decided that I should photograph as many as possible… These are absolutely incredible. Not necessarily intentional, but that is ultimately the meaning. Out of all of this disruption also comes something like this, where a town is trying to negotiate what it should look like in the moment that it is being boarded up.”

Photographer Robert Adams has written extensively on the nature of photographs and in particular on Beauty in Photography. In his essay by that same name, he explored the relationship between truth and beauty. Using Robert Capa’s famous photograph of a fatally wounded Spanish loyalist, Adams suggested that while the photograph may show truth and may reveal something very powerful, he did not believe it warranted the description of beautiful.

(Incidentally, the veracity of this particular photograph has been called into question. But, the legitimacy of the specific photograph and the nature of truth in photography is an exploration for another time.)

“For a truth to be beautiful,” Adams writes, “it must be complete, the full and final Truth.”

But, what is the “full and final Truth?”

I would suggest that the topics that Weems has chosen to wrestle with have no full and final Truth. Of course, there is the simple truth that racism and sexism are evil and morally repugnant. A lesser artist might be content to simply paint with such a broad stroke. But Weems is no lesser artist. Instead, she confronts us, the viewers, with truths that dig deeply into our country’s and our own complex relationship and history of racism and sexism. Yet, she does not lecture, as a lesser artist might also do.

Much of Carrie Mae Weems work melds words and images. It is a technique that is not unique to her, but her use of the written word is so artful that it transcends language, echoing and amplifying the visual. Completing, rather than competing, with the images.

Adams writes, “Photography’s abrupt rise also has to do, I suspect, with our distrust of language; the true outlines of wars and other barbarities have recently been obscured to an unusual degree by talk; maybe, we hope, we can find the Truth by just looking.”

Look at Carrie Mae Weems’ art and you may see the Truth.

Carrie Mae Weems: A Great Turn in the Possible at Amazon

Beauty in Photography, Robert Adams at Amazon

Robert Frank page on Amazon

Using these Amazon Links when purchasing books referenced here helps to support this website. Thank You!

There is a delightful talk by Carrie Mae Weems from the Art Institute of Chicago available on You Tube. Weems goes through many of the exhibits in the exhibition catalogue, adding context and background.