Kwame Brathwaite

There are few photographers who can lay claim to helping change national and even worldwide ideas surrounding human beauty. But, Kwame Brathwaite could legitimately be credited with playing a major role in redefining beauty.

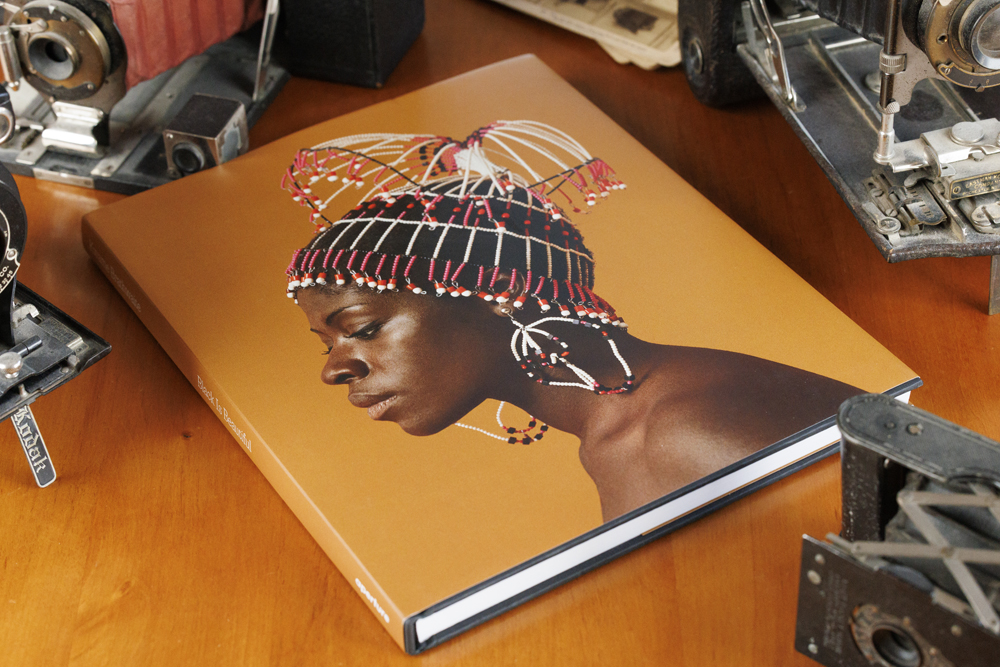

Black is Beautiful, tells the story of Brathwaite and showcases his photographs, which captured an era and served as a catalyst for change.

In the early 1960s when white standards of beauty thoroughly dominated the market to the exclusion of any other aesthetic, Brathwaite and his colleagues established the home-grown Grandassa Models, which championed a new aesthetic, “Black is Beautiful.”

But Brathwaite’s efforts were not confined to altering the way people judge beauty – as significant and revolutionary as that alone would be. It challenged the way America defined Black people and boldly empowered African-Americans to define themselves and defy the judgment of the dominant white corporate culture.

Born in Brooklyn in 1938, to immigrants from Barbados, Brathwaite’s own life coincides with much of the modern Civil Right movement. His parents moved to the Bronx shortly after he was born and Brathwaite was raised in an eclectic environment the included newcomers from Caribbean families like his own, Hispanic and Chinese immigrants and longtime Jewish, Irish and German residents of the neighborhoods.

As a teenager, Brathwaite found powerful influences that would intertwine and ultimately coalesce in his work – jazz, art, photography, civil rights and Black economic empowerment.

Brathwaite and his older brother, Elombe Brath, along with their circle of friends, were drawn to the modern jazz scene. The brothers would spend Sunday afternoons at the home of a family friend, Rosalind Harper, listening to and discussing her extensive collection of jazz records. Jazz was not just music to the brothers and their circle of friends; it was an art form and a political statement of Black pride and creativity.

Brathwaite’s parents had cultivated an appreciation of art in their sons, taking the family to places like Sag Harbor and Martha’s Vineyard in the summer, where they spent the days immersed in projects that developed their artistic creativity. Elombe and Kwame both attended what was then the School of Industrial Art (SIA) in Manhattan. Kwame studied advertising art, developing skills that he would put to work later in promoting jazz shows and eventually the Grandassa Models.

Seeing a friend taking photographs at a jazz show that he and his friends had promoted, Brathwaite was awed by the friend’s ability to photograph the performers using only existing light, without flash, thanks to the magic of Kodak’s fast Tri-X film (ISO 400) and the camera’s fast lens. Brathwaite soon bought a medium-format Hasselblad and set about mastering the camera and film, so that he could also capture the spirit of not only the jazz performers, but of the political currents that would define the 1960s.

In his Preface to Black is Beautiful, Brathwaite recalls seeing the graphic images of the martyred 14-year-old Emmett Till (Till was born in 1941, Brathwaite was born in 1938). He calls it a turning point in his life that prompted him to become an artist-activist.

“I focused on perfecting my craft so that I could use my gift to inspire thought, relay ideas, and tell stories of our struggle, our work, our liberation,” Brathwaite writes.

Inspired by the Black nationalist teachings of Marcus Garvey (also a product of the Caribbean, having been born in Jamaica), Kwame, Elombe and several friends started a social club which they named the African Jazz-Art Society. The AJAS melded two significant movements that fostered Black pride – jazz and Black economic empowerment.

The young men (Brathwaite was still in his teens), were frustrated by the migration of popular jazz from the Black neighborhoods to downtown. They wanted to make it possible for jazz fans to hear their music in their own neighborhoods and approached the owner of Club 845, a Bronx nightclub that had hosted acts such as Nancy Wilson, Thelonious Monk, Dinah Washington, and Dizzy Gillespie after World War II. By 1956 the club seemed past its prime.

The audacity of the AJAS members is impressive. They were all under 21 and had to enlist the older sister of one of the members to get a cabaret license. They then had to secure performers. Not an easy task for a bunch of teens with no show business connections. No agent would consider them, so they went directly to the musicians – staking out a restaurant popular with band members on Saturday mornings after the performers finished their Friday night gigs.

They knew they couldn’t get the band leaders, but they found they could get the musicians who were willing to pick up a few extra dollars on the side on a Sunday night.

Brathwaite’s skill as a photographer was put to use taking photos of patrons dressed in their most impressive clothes for a night on the town. These concerts allowed Brathwaite to perfect his own skills, shooting images of jazz performers and club patrons that captured the essence of cool.

But, as much as Brathwaite and his colleagues loved jazz, it was not simply the music but the social significance and power that jazz embodied that inspired AJAS.

Kwame and Elombe had heard Carlos Cooks, a follower of Marcus Garvey, years earlier and joined Cook’s African Nationalist Pioneer Movement (ANPM) formed after Garvey’s death. The organization promoted racial pride, economic autonomy, self-help and independence, all of which melded perfectly with the work of the AJAS and the spirit of jazz.

Cook’s mantra of “buying Black” resonated with Kwame and Elombe, who were well acquainted with the value of Black business ownership, given that their own father had built a successful dry cleaning and tailoring business serving mostly Black neighborhoods.

But, beyond “Buying Black,” Brathwaite and the other members of the AJAS took to heart Cooks’s mantra to “Think Black.” That included being politically aware and concerned with issues challenging the Black community, as well as adopting styles that reflected a pride in their African heritage.

From there it was a short leap for the AJAS to expand their mission to promoting African-inspired products and encouraging more natural styles of dress that challenged traditional white-imposed European standards.

They drew on the term Grandassaland, that Carlos Cooks had used to describe Africa, to form a modeling troupe of both men and women that they called Grandassa Models. They changed the name of AJAS to AJASS (African Jazz-Art Society and Studios) to reflect its broader mission.

Brathwaite’s photos and the Grandassa models, with their natural hair styles, dresses in bold African-inspired prints and intricate beaded jewelry helped promote and definitively prove that Black is Beautiful. More than just a superficial reference to physical appeal, the message that Brathwaite carried through his photographs was that culturally, intellectually, historically and socially, embracing the African-American culture was beautiful and a source of pride.

Today, diversity in advertising has long become mainstream. Brands compete with one another to demonstrate which can project the strongest image of diversity. Models of color are no longer confined to specialty markets, but found throughout mainstream media. In 2021, when model Leyna Bloom appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue, it was notable not because of the color of her skin, but because she was the first transgender model to make the cover.

That might have seemed inconceivable in the 1960s, but the work of Brathwaite and his colleagues through the African Jazz-Art Society & Studios help set the world on a path that continues today.

Black is Beautiful is a book about Brathwaite and his photography that captures an insider’s view of a movement that helped spur major changes in American culture. But it is also a personal, visual diary of someone who lived through and helped effect those changes.

Black is Beautiful on Amazon.

Using these Amazon Links when purchasing books referenced here helps to support this website. Thank You!