Dauwood Bey: A Portrait Artist in the Documentary Tradition

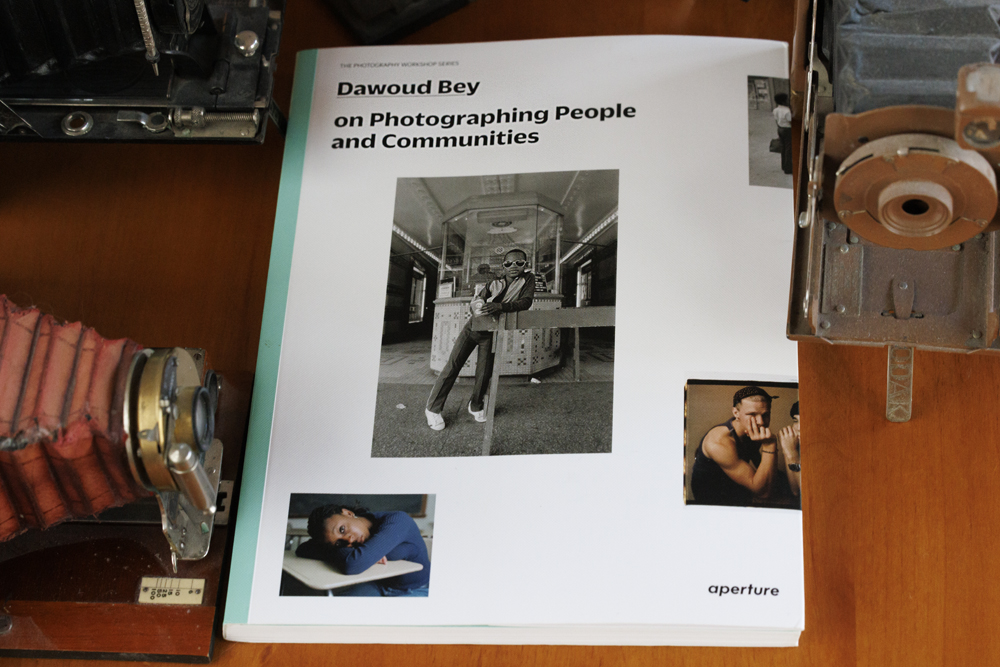

I previously wrote a brief commentary on the Aperture Photography Workshop Series book featuring Dawoud Bey.

One of the beauties of the Workshop Series is that they pair images by the featured photographer with commentary from the photographer on the images, what they were trying to say and how they went about doing it. I’m not really sure that I can add much to that. Bey’s own words are far more powerful and insightful than anything I can add, especially when coupled with his images.

Instead, I’ll provide some brief biographical information about Bey, along with a short summary of some of his major projects.

Born in Queens, New York, in 1953, Bay received his first camera at age 15. Bey cites Roy DeCarava and his book “The Sweet Flypaper of Life” (written in conjunction with poet Langston Hughes) as critical inspiration for his own work.

A quick detour here: DeCarava (1919-2009) began his career as a painter and printmaker and took up the camera as a way to make visual notes for future work. But, as he photographed, he became fascinated with the possibilities presented by the camera. DeCarava rejected both photojournalism and street photography, feeling that the first was too cold and the second because it sacrificed the individual identity and personality of subjects.

According to photography historian Mary Warner Marien, DeCarava in his application for a Guggenheim Fellowship (Awarded in 1952 and the first ever received by a Black photographer) wrote that he wanted to show “the strength, the wisdom, and the dignity of the Negro people.”

DeCarava’s influence can easily be seen in Bey’s own portraits, which treat every subject as a unique and complex individual, never reducing them to a “type.”

In his project Class Pictures, Bey photographed teenagers from schools across the country, using a 4×5 camera and shooting with Polaroid color film. According to Bey the project began with three Chicago schools: The University of Chicago Laboratory School; Kenwood Academy, which is a magnet school; and South Shore High School, a public school.

For each portrait, Bey would first ask the students to write a brief autobiographical statement. Bey would take their portraits before reading the statements, but when the photographs were displayed and later published, each portrait was paired with the student’s statement.

While the project began in Chicago, Bey continued it, first during a residency in Detroit and eventually in seven cities around the country. Taken together, the portraits and accompanying text paint a picture of youth at the turn of the 21st century that is nuanced and diverse. For most of the 20th century teenagers have been among the most oversimplified and exploited subjects in photography. Even more so with teens of color or with teens who do not conform to adult ideals of dress, attitude or behavior – which is to say, most teenagers.

A common trope in the media, which seems to be repeated with every generation, is that the youth of “today” personify all that is wrong with society. That they are proof that the country is going to hell in a handbasket.

Bey’s project neither romanticizes nor indicts the youth he photographed, but rather presents them as they are – young human beings on the threshold of adulthood. Young people experimenting with their own identity as they work out who they will become when they cross into the world of adults.

I had the good fortune to spend my final years before retirement photographing at a small majority Black college. There were aspects of the job that I did not love, but my interactions with the students were always a joy. It is a great privilege to be in your late 60s and get a daily glimpse and reminder of what it is like to be stepping into the adult world, full of dreams and hope. It was an even greater privilege as an old white guy to get a glimpse into the lives and culture of young Black men and women coming of age in the 21st Century.

While photographing basketball games and other sports, one of my favorite thought experiments was to look at the parents in the stands. I would think of my own daughters, now older than these students, and fondly remember holding and rocking them. I would remind myself that each of these tall, muscular fearsome athletes had, not that many years ago, been a baby held in their parents’ arms.

I think many of our problems, many of the catastrophic shootings of young Black men, the excessive incarceration of people of color, might be avoided if more people in positions of authority would recall that just a few short years ago, they were babies held in the arms of their parents.

One of Bey’s most moving projects recalls and reinterprets the 16th Street Church bombing that occurred on Sept. 15, 1963 in downtown Birmingham, Alabama.

At about 11 a.m. on Sunday morning, a bomb exploded under the steps of the church, killing three 14-year-old girls, Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair and Carole Robertson, along with 11-year old Cynthia Wesley. Later, in the aftermath, two boys were killed. Johnny Robinson, 16, was shot in the back by a police officer, who claimed the boy had been throwing rocks at a car draped in the confederate flag. The other boy, Virgil Ware, 13, was riding on the handlebars of a bike his 16-year-old brother was pedaling when two white teenagers shot and killed the younger Ware.

For his project Bey took portraits of subjects who were the same age as the victims at the time of their death and portraits of subjects who were the same age as the victims would have been at the time of the photographs. He paired the images, graphically and movingly illustrating just how young the victims were and how they had been robbed of the opportunity to grow old. Looking into the eyes of the older stand-ins for the victims, I can only think about the tragedy of the lost years. How the actual victims were robbed of the opportunity to finish school, get married, take a job and live their lives.

If the power of photographs as documents can seem to be fading today, in favor of photographs as works of art, Bey’s work reminds us that the most powerful and the most timeless photographs still remain those that show us the world as it is.

Dawoud Bey on Photographing People and Communities, Aperture Photography Workshop Series, on Amazon.

Dawoud Bey page on Amazon.

The Sweet Flypaper of Life by Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes on Amazon.

Aperture Photography Workshop Series on Amazon.

Using these Amazon Links when purchasing books referenced here helps to support this website. Thank You!