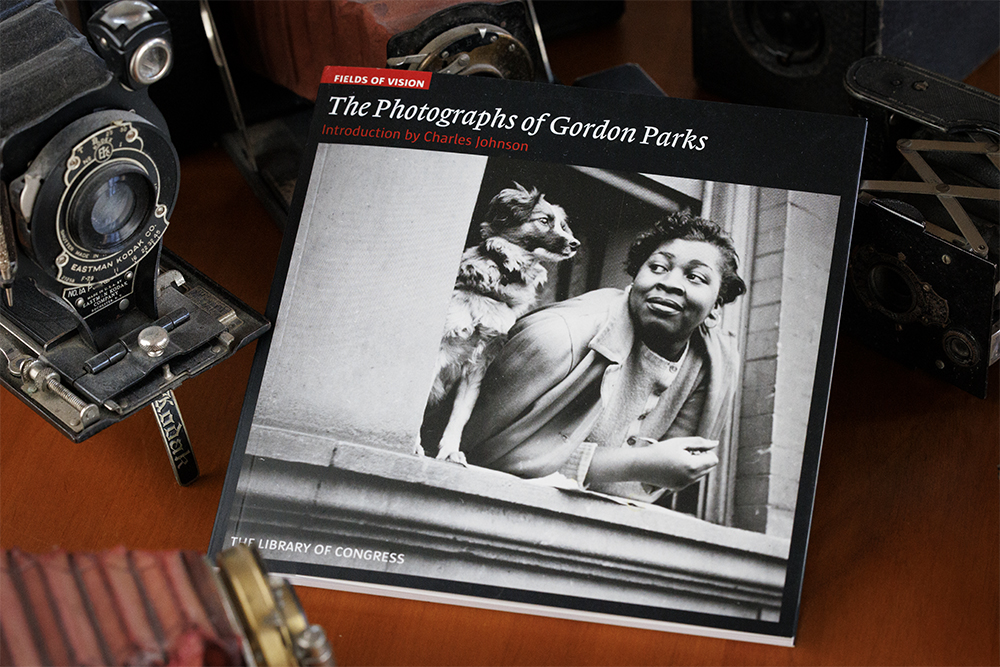

Fields of Vision: The Photographs of Gordon Parks

Chances are, if you asked the average person to name a renowned African-American photographer, Gordon Parks, would be at or near the top of the list (that is, of course, if the average person could name any African-American photographer).

The term Renaissance Man is often overused and handed out lightly, but in the case of Parks, it’s hard to think of a better description. Photographer for Life, Vogue and Glamour, author of the autobiographical classic The Learning Tree, writer of the libretto and music for the ballet Martin and director of the movie version, and director of the classic genre-creating film Shaft, are just a few of his accomplishments.

But, before all that, Parks was the first and only African-American photographer to work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the storied New Deal government agency that produced some of the most iconic photographs and photographers of the 20th century. Photographs from Parks time at the FSA are included in the fifth volume of the Library of Congress Fields of Vision series.

So significant was the work of FSA photographers that any mention of the Great Depression is likely to conjure up a mental picture drawn directly from images by FSA photographers. Readers who are even remotely aware of the FSA, are likely to recognize some of the photographers, including Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, Ben Shahn, Jack Delano and Russell Lee.

Parks arrived late in the history of the FSA, in 1942, when he was 30 years old and just as the agency was about to be absorbed into the Office of War Information.

Though his time at the agency was brief, Parks produced powerful and iconic images while there. The best-known and probably most often reproduced image was shot shortly after he arrived, that of charwoman Ella Watson, which Parks titled “American Gothic, Washington, D.C.”

The image shows Ms. Watson in the building that housed the FSA. It was taken after everyone else had left for the day and she is posed in front of an American Flag, with a broom in one hand and a rag mop standing on the other side.

The image has been reproduced many times and is included in the Fields of Vision series book on Parks, published by the Library of Congress. Fields of Vision is an excellent series that features the work not only of Parks, but offers volumes on most of the FSA photographers.

The Fields of Vision book recounts how Parks started a conversation with Watson, and “over the course of an hour, she took him through her ‘lifetime of drudgery and despair.’” That may be a questionable assessment, as interviews with family and friends of Watson indicate that she was a woman of deep faith and deep love for her family that brought her great joy. She is remembered as having a dignity that overshadowed her humble lifestyle.

Nearly half of the photographs in the Park’s volume of Fields of Vision, were taken in Washington, D.C. Individually and collectively they present a powerful portrait and indictment of race in America’s capital city. It’s clear from Park’s images for the FSA that he was keenly aware of the irony of Black Americans living in poverty and oppression in the seat of government.

The images, as was typical of the FSA style, are paired with simple, understated descriptions. Typically, the descriptions were provided by the photographers.

“Young boy, whose leg was cut off by a streetcar while he was playing in the street, standing in the doorway of his home on Seaton Road in the Northwest section, Washington, D.C., June 1942.”

“Wooden privies in the Negro area, Washington, D.C. (Southeast section), November 1942.”

“Johnny Lew, owner of the laundry under the apartment of Mrs. Ella Watson, a government charwoman, Washington, D.C., August 1942.”

“Reverend Vondell Gassaway standing in a bowl of sacred water banked with the roses that he blesses and gives to celebrants, Washington, D.C., August 1942.”

I’ve read dozens of these descriptions from FSA photographers and they could be used in a master class on how to caption photographs to explain and amplify images in the fewest words.

By the time Parks had arrived at the FSA, the mission of the agency had evolved from its early days, when many of the photographers concentrated on the crushing poverty brought on by the Depression. As the country recovered and as the threat of war increased, the photographs began to reflect those changes.

Esther Bubley, another late addition to the Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information, did not ignore the poverty in America, but she also photographed teens jitterbugging, a girl listening to the radio in her boarding house room, a high school student’s saddle shoes and another high school girl holding a tennis racket and tennis balls while waiting for a tennis court.

Virtually all the FSA-OWI photographers seemed keenly aware of the racial divide in America and produced pictures that were clear indictments of the treatment of Blacks. But Parks was uniquely qualified to articulate the inequities and ironies of America’s treatment of its minorities during the depth of the Jim Crow era.

What is striking about many of Park’ photographs from the FSA is that they are not simply one-dimensional portrayals of victims of racism.

Another photo in the collection shows Watson’s adopted daughter. The girl half-sits on a bed’s metal frame, one foot planted on the floor and the other resting on the bedframe. Despite the humble surroundings, she is impeccably dressed – plaid skirt and jacket and starched white shirt.

No one who looks at this portrait, the portrait of Ella Watson, or that of her downstairs laundry man Johnnie Lew, can deny the dignity of these people. Lew stands in his crowded shop, neat stacks of folded and packaged laundry fill three shelves next to him and in the background, over his shoulder there is an American Flag.

When Parks photographed a Black police officer in New York, the officer stood in front of tenement apartments in a perfectly pressed uniform. His eyes look over the neighborhood, not as an antagonist, but as a guardian of the people and the neighborhood.

In Washington, Parks photographed two African-American firefighters playing checkers at their firehouse. He photographed another Black firefighter in uniform, arm resting on a fire truck. He photographed a Black woman playing piano at the Church of God in Christ.

Parks did not shy away from the poverty that trapped – and continues to trap – so many people of color in America. But, Park’s photos do not simply show victims. By seeking out the dignity and humanity of his subjects, he humanizes his subjects while underscoring the inequity that undermines the egalitarian goals of America.

Parks did not work for the FSA for long – when it was absorbed into the Office of War Information in 1943 he was embedded with the pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group (part of the Tuskegee Airmen).

During his time at the FSA he photographed Duke Ellington in New York, Mackerel fishermen in Massachusetts, the Fulton fish market in New York, Ag students working a plow in Daytona Beach, Florida and residents of Harlem.

Clearly though, Parks dove deep into documenting Ella Watson and her circle. From a 2018 essay in the New York Times by Deborah Willis, I learned that Watson was something of a muse for Parks. During his brief time at the FSA he made more than 90 photographs of her.

Another image from Ella Watson’s apartment shows her dresser topped with six religious statues, including a small one that is also certainly Martin de Porres, the mixed-race Peruvian saint. Hanging from the mirror is a rosary, while a small crucifix sits on the dresser top, along with two votives and several other candles. Intriguingly, reflected in the mirror are two young children.

Willis also wrote that Watson spent much of her life caring for her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Another image, not reproduced in Fields of Vision, shows the same dresser, but this time Parks adjusted his lens to focus on the two children. Visible behind them is Ella Watson, who appears to be tending to the older child’s hair.

Looking at the rosary and statuary gives the impression that Watson may have been Catholic. Actually, she belonged to St. Martins Spiritual Center, which was founded by Rev. Vondell Gassaway – the minister pictured somewhat mysteriously standing in that “bowl of sacred water banked with the roses.”

It turns out that that bowl was part of an annual “Flower Bowl Demonstration” in which church members removed their shoes, because during the service they walked on “holy ground.” The church was one of a many Spiritualist churches that that arose during the Great Depression and incorporated Pentecostal, African and Indigenous rituals in Christian service.

Parks natural empathy for his subjects, and the skills he honed in his work for the FSA that enabled him to convey that empathy through photographs would serve him throughout his career.

In 1961, Parks produced one of Life Magazines most remembered stories of the time: documenting life in a squatters’ community outside of Rio de Janeiro. There are echoes of Ella Watson in the story, which focused largely on twelve-year-old Flavio Da Silva, the oldest of eight children. Sick with asthma, he cared for his siblings while his parents spent their days scavenging for food to feed the family. Parks photos proved so powerful that within a month of their publication, readers were so moved by Flavio’s story that they raised enough money to allow Parks to take Flavio to an asthma clinic in Denver for treatment.

The FSA photographs represent only a brief time in the long career of a photographer, author, poet, composer and film director who died at the age of 93 in 2006. But, to appreciate the life and career of Gordon Parks, his work at the FSA provides a powerful and crucial starting point.

The Photographs of Gordon Parks: The Library of Congress (Fields of Vision) at Amazon.

Gordon Parks Page on Amazon.

Using these Amazon links when buying books helps support this website. Thank You!

Things as they Are: Photojournalism in Context Since 1955 on Amazon.

This is a fascinating book for anyone interested in photojournalism. Jointly published by Aperture and World Press Photo, it reproduces major stories from 1955 to 2005 exactly as originally printed, including Park’s 1961 Life Magazine story featuring Flavio and his life in Rio de Janeiro.

I intend to write a more thorough discussion of the book soon, but in the meantime, I highly recommend it.

Using these links when buying recommended books helps support this website. Thank you!