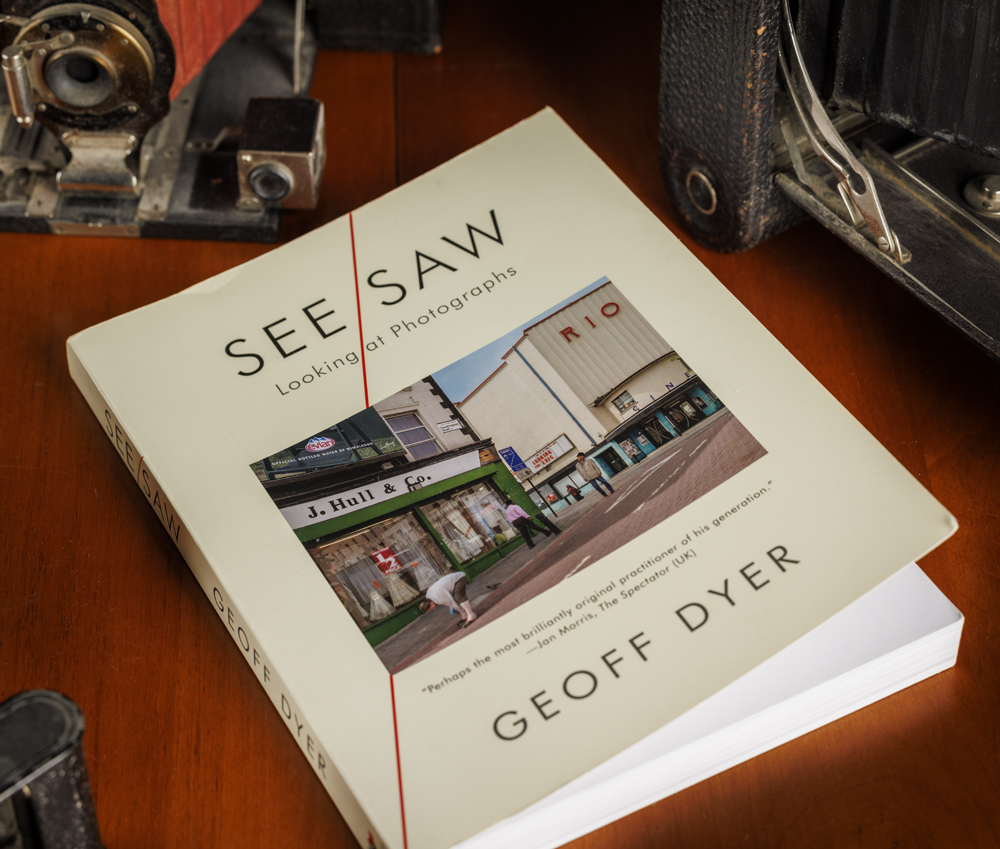

See/Saw by Geoff Dyer

In The Ongoing Moment, Geoff Dyer took readers on a stroll with some of photography’s greatest artists, looking at why and how so many subjects repeat themselves in the work of so many different photographers. He noted how certain themes – park benches, gas stations, roads, fences, nudes, the poor, for example – have drawn the attention of photographers throughout the 20th century and into the 21st. And, how photographs on those themes have differed wildly at times and at other times converged.

If The Ongoing Moment focused on the gods and goddesses of photography, then See/Saw: Looking at Photographs features mostly demigods (with a few notable exceptions). You won’t find an Edward Weston, Paul Strand, Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Henri Cartier-Bresson, or Diane Arbus in this book.

But that is hardly the only, or even main, difference between the two books. If The Ongoing Moment is a relatively straightforward story of photographers and photographs (with many detours to connect the dots), See/Saw is a much more personal, introspective, and at times, idiosyncratic look at photographs.

Many authors have tackled the idea of looking at photographs. That’s hardly surprising. It’s the main occupation of critics and curators. John Szarkowski set the model in 1973 with Looking at Photographs, which drew 100 pictures from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Each image was accompanied by a commentary that sought to put the image into context, tell readers a bit about the artist and explain the significance of the picture.

The difference from this traditional approach is that in See/Saw we get a lot of Geoff Dyer as well.

Dyer may take the artist’s background, significance and intent as a starting point, but often uses his essays to expound on his own observations. In a sense, the book might be just as easily titled See/Saw: Geoff Dyers Looks at Photographs and Tells You What He Sees.

Not that that is a bad thing. Dyer is an insightful and extremely well-educated critic. He has authored books on the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier, on aging in athletes and artists, on World War I, on jazz and on film, to name just a few. He has written fiction and non-fiction.

At times, I was more than a little intimidated by his encyclopedic knowledge not just of photography, but of art and the world.

That’s not to say that he makes the reader feel ignorant. His writing style is down-to-earth and accessible. It’s a bit like having a conversation with a respected scholar and realizing part way through how much you don’t know and how generous it is that the person you are talking to really seems not to notice what an uneducated fool you are.

Dyer’s book is actually divided into three very unequal parts. The first section is entitled “Encounters” and features multi-page essays focused on individual photographers. I’ve used the term demigods to describe these photographers but I don’t wish to denigrate or minimize their talent or significance. It might seem odd or a bit ridiculous to refer to a photographer like Andreas Gursky as a demigod, given that for more than a decade his Rhein II held the world’s record for the highest price paid at auction for a photograph. ($4.388 million).

Gursky may be among the best known, but most of these photographers can be found in any decent history or survey of photography and most readers will be aware of at least some of them. But they are not necessarily among the handful that virtually everyone is familiar with. Some photographers are well known, some are likely to ring a bell, but there are also photographers whom no one should feel embarrassed to admit they aren’t familiar with.

“Encounters” is an appropriate term because these essays really do seem to be an encounter with the photographer by Dyer. Sure, Dyer tells us about the photographer and his or her photographs, but he also is unafraid to meander down paths that reveal himself and his own reactions and responses to photographer and photograph.

Unfortunately, each essay is usually accompanied by only one image from the photographer’s repertoire. I suspect, but do not know, that the choice was probably made in order to allow for the best quality reproductions in an affordable format. And, the reproductions are very good.

The second section, “Exposures,” is a collection of 10 essays written between 2013 and 2014 and drawn from Dyer’s “Exposure” column written for the New Republic. In each piece Dyer selected a news photo and wrote a brief essay on the photo. I found these to be the most enjoyable pieces in the book.

Finally, Dyer includes three columns on three different photography critics, Roland Barthes, Michael Fried and John Berger.

Having attempted on multiple occasions to slog my way through Fried’s Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before, I admit I took great pleasure in Dyer’s merciless takedown of Fried. Dyer describes Fried’s writing as “some of the most self-worshipping – or, more accurately, self-serving – prose ever written.”

When confronted with an opus like WPMAAANB, that the modern art establishment has apparently declared to be significant, it was nice to know that it isn’t just me who finds it nearly unreadable. I felt like the book should actually come with a longer title: “Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before and Why Art Matters Less than Ever Before.”

But that may also be a symptom of my own bias regarding much of today’s art photography. The internet in general and social media in particular has unleashed a flood of creative personal expression. The result has been an art establishment that often feels too desperate to remain relevant and unable to exert the influence it is accustomed to – much like the academies at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century.

I get that same feeling with nearly every issue of Aperture magazine –trying so hard to be on the cutting edge while at the same time making sure they can milk luxury advertisers by selling themselves as the sort of magazine that the Real Housewives of Beverly Hills will be sure to display on their coffee tables, right next to a copy of Why Photography Matters…

Second acts are difficult and I think See/Saw suffers a bit in comparison to The Ongoing Moment. In part because it is a very different book and it takes some work to wrap your head around that. Dyer shouldn’t be criticized for choosing not to repeat himself and, judging the book on its own merits there is a lot to recommend it.

Circling back to my original observation about demigods, one of the biggest strengths of See/Saw is that it offers the reader a, perhaps unintentional, introduction to great photographers that stand at the edge of immortality. Not quite assured that they will live forever in the pages of future histories of photography but not yet discarded by the art world in favor of the next big star. Many of these artists don’t get the recognition their work deserves, and Dyer has provided a great service by reminding us all that there are many photographers whose work is worthy of thoughtful looking.

See/Saw at Amazon

The Ongoing Moment at Amazon

The Photographer’s Eye (John Szarkowski) at Amazon