The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

In introducing the work of Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand through the New Documents exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1967, curator John Szarkowski heralded the three as part of a new generation of photographers building on the documentary approach “toward more personal ends.”

He declared that their aim was “not to reform life, but to know it.”

Arbus, in particular, was drawn to those living on the edge of society, photographing transvestites, side-show performers, female impersonators and nudists. Even when photographing “ordinary” people, Arbus had a knack for emphasizing a sense of the otherness separating individuals from the larger society.

Yet, Arbus was always the observer and her pictures can feel voyeuristic. Whether or not that is a fair criticism, it is certainly true that when we view an Arbus picture the image and frame separates us from the subject. We are visitors to, not residents of, their world.

In 1971, Diane Arbus wrote “Last Supper” in her diary, took an overdose of barbiturates, climbed into her bathtub and slit her wrists. That same year, Nan Goldin began to photograph.

If Arbus used the photographic document to illuminate those who lived at the edges of society, Nan Goldin took the next step, creating a document not of others, but of herself and her friends, who were living at the edges of society.

Goldin observed, “There is a popular notion that the photographer is by a nature a voyeur, the last one invited to the party. But I’m not crashing: this is my party. This is my family, my history.”

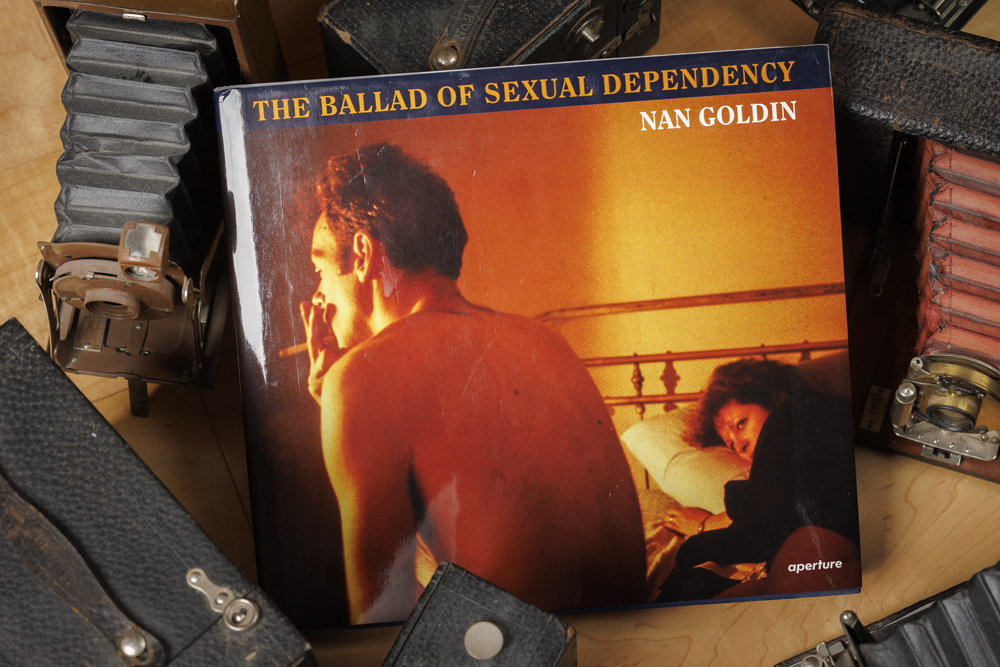

Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency began as a slide slow, comprising between 700 and 800 slides that she took to took to clubs and other venues around New York. Goldin described the Ballad as “the diary I let people read,” writing that “My written diaries are private: they form a closed document of my world and allow me the distance to analyze it. My visual diary is public…”

In 2012 Aperture Foundation republished The Ballad of Sexual Dependency adding a new afterword by Goldin. It is still available and can be found on Amazon.

Goldin’s “public diary” is candid, unguarded and deeply personal. It’s hard to fathom what a written diary could include that her visual diary might not.

One of the most reproduced photos in the Ballad is a self-portrait “Nan after being battered, 1984.” She stares unflinchingly into the camera, one eye is swollen and black and blue, there appears to be a bruise under her other eye. The picture tells a personal story, but it also tells a story repeated over and over across ages involving many different women in many different situations that are at once different and the same.

From that picture, it would be easy to stereotype The Ballad of Sexual Dependency as a story of sexual violence between men and women.

But, through her introductory text, Goldin made clear she was after a much more complicated and nuanced depiction of sexual dependency.

Goldin is an astute observer of human relationships, writing, “I often fear that men and women are irrevocably strangers to each other, irreconcilably unsuited, almost as if they were from different planets.” This, long before the 1992 publication of Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus.

It’s actually worth quoting more extensively from Goldin’s original introduction to better capture her intent.

“…there is an intense need for coupling in spite of it all. Even if relationships are destructive, people cling together. It’s a biochemical reaction, it stimulates that part of your brain that is only satisfied by love, heroin, or chocolate; love can be an addiction. I have a strong desire to be independent, but at the same time a craving for the intensity that comes from interdependency…”

“…Sex itself is only one aspect of sexual dependency. Pleasure become the motivation, but the real satisfaction is romantic. Bed becomes a forum in which struggles in a relationship are defused or intensified. Sex isn’t about performance; it’s about a certain kind of communication founded on trust and exposure and vulnerability that can’t be expressed any other way…”

Goldin was 11 years old when her 18-year-old sister went to the commuter rail tracks near their home outside Washington, D.C., laid down and waited for the train to come. It was an act that Goldin described as one of “immense will.”

“I saw the role that her sexuality and its repression played in her destruction. Because of the times, the early sixties, women who were angry and sexual were frightening, outside the range of acceptable behavior, beyond control,” Goldin wrote.

“In the week of mourning that followed, I was seduced by an older man. During this period of greatest pain and loss, I was simultaneously awakened to intense sexual excitement. In spite of the guilt I suffered, I was obsessed by my desire.

“My awareness of the power of sexuality was defined by these two events. Exploring and understanding the permutations of this power motivates my life and my work.”

“Seduction” seems an odd way to describe an 11-year-old’s sexual exploitation, but it illuminates one of the interesting things about Goldin and her work. No matter how victimized she may have been, Goldin refused to see herself as only a victim.

In a 2012 Afterward for the new edition of Ballad Goldin took issue with the stereotyping of her subjects and her work, “They talk about the work I did on drag queens and prostitution, on ‘marginalized’ people. We were never marginalized. We were the world. We were our own world, and we could have cared less about what “straight” people thought of us.”

One of the strengths of Goldin’s Ballad is that her photographs reveal a fascinating mixture of objectivity and subjectivity, often both at the same time.

It is tempting to credit Goldin’s compulsive documentation of her life and her friends as a precursor to the ubiquitous self-documentation found today on Instagram and Twitter. But Goldin documented a generation and world far removed from today’s social media. Her world was populated not by “influencers” but by young men and women who had left or been driven from their homes and often lived an existence fueled by drugs, alcohol and sex, not in the glamorized, Hollywood rewritten style, but in the reality of cluttered, dingy apartments with unmade beds, unwashed linens, leaking pipes, second-hand furniture and rooms with lead paint peeling off the walls.

Goldin says one of her motivations to document herself and her friends was simply to be able to remember what had happened – to cut through the fog of drugs and alcohol from the previous night.

It’s possible to draw a progression and contrast by taking a brief look at another photographer, Ryan McGinley, who serves as something of a link between the years. McGinley also set about documenting his friends in the late 1990s and early 2000s. He was as obsessive as Goldin, spending about five years taking Polaroids of anyone who visited him and his friends in Greenwich Village. There is plenty of nudity and sex in McGinley’s photographs as well. But his images seem to have an air of kids out on an adventure – as though they are cutting loose during some extended spring break traveling cross country.

In fact, in the early 2000s that was exactly what they were. He packed eight friends, plus two assistants, into two vans and drove from coast to coast and back, photographing. McGinley’s odyssey was a mix of personal documentary and commercial photo shoot – he paid his companions a day rate, covered their food and lodging and paid for their flights home. Investing about $100,000 for each trip.

McGinley’s subjects knew they were part of a performance. That’s not to say that the pictures aren’t candid or authentic, but it is to acknowledge that his friends were co-creators and it is difficult to separate the real from staged – perhaps because they saw all of life as a stage.

Goldin’s friends were no doubt aware of her obsession with photographing them, but they never appear to be performing for the camera.

And that, I believe is what anchors her images to their era.

As my own career transitioned toward retirement, I spent several years photographing at a small college. One thing that I noticed among all the students, regardless of race, nationality or background, was that they were closely attuned to their own photographic image. From years of selfies, most knew exactly how they wanted to present themselves to the camera. Almost any of them could have walked onto the set of a photoshoot and given a spot-on performance as a model.

This is a generation that is acutely aware of how they look when photographed. If Garry Winogrand took pictures to see what things looked like when they were photographed, today’s generation seems to live life in order to see what their lives look like photographed.

Would it even be possible today to capture the same raw, unscripted lives that Goldin produced for her visual diary? Certainly there are plenty – too many in fact – young people today living lives fueled by opioids, alcohol and sex. And, given how ubiquitous smart phones are, it is likely that some of them are documenting their lives. But, would it have the same resonance that Goldin captured in her work? I am not sure.

Neither, apparently is Goldin. With the reprinting of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency Goldin produced an Afterword in 2012.

She wrote, “Way before social media, Ballad – which comprises fifteen years of work – allowed that documenting one’s own life experience is as valid as documenting people and cultures one does not know. But now, I am terrified that everything I believe about photography, about this work, is over because of the computer and the easy manipulation of images it facilitates. This work was always about reality, the hard truth, and there was never any artifice. I have always believed that my photographs capture a moment that is real, without anything set up. This is at the core of my practice, and I continue to work this way today.”

I am not sure that it is Photoshop that should be feared. Perhaps instead we should fear that social media is creating a culture that, instead of living, propels us to simply perform and share those performances in imitation of life.

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency on Amazon

Nan Goldin on Amazon

Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus on Amazon

Ryan McGinley on Amazon

Using these Amazon links when buying books helps support this website. Thank You!